For this church:    |

|

Lisors Lisors |

The next documentary reference to Fledborough appears to date from 1166, when the bishop of Lincoln certified that three knights’ fees were held from him by Nigel de Fleuburge, who may have descended, possibly in the female line, from the Nigel who had been the bishop’s tenant in 1086. Nigel de Fleuburge is thought to have been the father of Robert de Lisures, who held the same three fees in 1201 and 1210. The Lisures family came originally from the village of Lisors, near Rouen. It remains an extremely picturesque spot, deep in the Normandy countryside, with a church whose surviving fabric dates from the 15th century. Carter and Wilkinson draw a parallel with Fledborough, on the grounds that Lisors is very small and remote. This is somewhat misleading in that Fledborough was not particularly small or remote by the standards of the time – in fact, situated on the River Trent, which by this time was being used regularly for the transport of raw materials and merchandise, it was probably less remote than much of Nottinghamshire.

Fouque de Lisors took part in the 1066 invasion, probably in the company of Roger de Busli, and was subsequently noted in Domesday Book, along with his brother Torald, holding considerable lands in Cottam, Eaton, Harworth, Marnham, Clayworth, and Clarborough. Both Fouque and Torald were witnesses to the foundation deed of Blyth Priory in 1088, and they were subsequent benefactors.

The branch of the family which remained in Normandy also supported the Church. Near to Lisors in Normandy is the Abbaye de Mortemer, a Cistercian foundation dating from 1134 and built on Lisures land. In 1164 Hugues de Lisors is recorded as making a grant to the monastery, of which he became a monk. References to the Lisures family in Normandy cease in the early 13th century, suggesting that the family emigrated or lost their possessions after Normandy was conquered by the king of France in 1204.

Robert de Lisures was probably the father of Nigel de Lisures, who is recorded as having held three knights’ fees from the bishop of Lincoln in 1242-3. Nigel was prominent in the county, having been appointed a justice of assize in 1230 and continuing in this role for about twenty years. He was the father of another Nigel de Lisures, who is recorded as having presented Hugh de Normanton, who was a canon of Lincoln, as first Rector of Fledborough in 1287. The church had been sequestrated and upon his appointment archbishop Johne le Romeyn granted custody to Hugh; he was was also granted protection with clause nolemus by Edward I in 1295 for having given a tenth of his benefice to the king. Nigel died in about 1290 and in 1291 the church was valued at £13 6s. 8d. Nigel de Lisures was succeeded by John, possibly his son but more likely his brother, since he is recorded from 1274-5 as having stopped up a pathway in Fledborough which ran outside his croft. John de Lisures is thought to have been the ‘John de Lisors’ who represented Nottinghamshire in the parliament of 1302, and also the ‘John de Lyseus’ recorded in the same year as holding one knight’s fee in ‘Fledburg, Normanton and Wodecotes’.

This appears to be the earliest reference to Woodcoates. It means ‘cottages by the wood’ and is evidence for a subsidiary hamlet about 3km west of Fledborough, now indicated only by earthworks. This is presumably where the wood pasture 1 league long and ½ league wide, noted in Domesday, was located. In 1399 it was described as the 'chapelry of Woodcoates' by Archbishop Richard Scrope who appointed Master Richard Arnall, rector of Barton-in-Fabris, to hear and proceed in a cause concerning the failure by the rector of Fledborough, Robert Grene, to provide a priest to celebrate three days each week in the said chapel.

Sir Hugh de Normanton was still the rector in 1301 when Archbishop Thomas of Corbridge instructed his commissary, Master J de Roderham, not to molest Sir Hugh for non-residence or contumacy. In August the same year the archbishop issued a mandate to Sir Hugh to enquire who were receiving the profits of the land and mill given by Master Alan de Wympton for the support of a chantry in the chapel of the Blessed Virgin Mary at Wympton.The John de Lisurs who represented Nottinghamshire in the parliaments of 1312 and 1315-6, is likely to have been the son of the above. He was one of the commissioners charged with raising forces in the county in 1316 for Edward II’s intended expedition against Scotland, and in 1328 he was described as a knight. The earlier of Fledborough’s bells may have been his gift. He was succeeded by his son, another John, who is first recorded by Dugdale in 1339-40 as ‘Sir John Lizours’. It is recorded that in 1343 he received a licence for alienation in mortmain, of a messuage and land in Fledborough to a chaplain to celebrate divine service daily in the chapel of St Mary in the parish church, for his soul and for the souls of his father, mother, ancestors and heirs. The first chaplain was William Allotts of Ragenhall, who was to live in a house in the village between the dwellings of Richard Madour and Thomas, son of William. The land lay scattered in the village’s open fields – 9 acres and a headland of 3¼ roods in Hamelthorne, 4 acres and a rood in Harethorne, 3 acres in Crossewonge, 6 acres and 1¼ roods in Wodebekhill, 7 acres 2½ roods in Arkehill, and 4 acres in the Long Wonge. The effigy of a knight may represent Sir John and that of a lady is thought to depict Clemence, his mother or wife. Both are now in the north aisle, but originally they were probably located in the chantry chapel. Sir John took part in Edward III’s campaign in northern France, and fought at the Battle of Crècy on 26th August 1346, where he appears to have served under the Earl of Warwick. He may have distinguished himself in the battle or at the subsequent siege of Calais, for in November 1346 he was licensed by the Crown to appropriate the church of Fledborough to certain chaplains to celebrate divine service in perpetuity as he should order, effectively giving Sir John the right to convert the church into a private chapel. He lived until 1363 or 1364, and was succeeded by his younger son James, who is thought to have died childless, shortly after his father.

In 1334 the rector of Fledborough, Richard de Glatton, was granted licence by Archbishop William Melton to be absent until 24 June the following year in order to go on pilgrimage to St James of Compostella.

In 1341 the nonae rolls record that Fledborough was taxed at 20 marks (£13 6s. 8d.) and that the ninth of sheaves, lambs and their fleeces were worth 15 marks (£10) a year at true value and no more, and that the arable land and meadow there were worth 15s. a year, and the tithe of hay with altar dues was worth 26s. 8d. a year.

In the event that his sons predeceased him or died without issue, Sir John had in 1357 entailed his estates to William, son of Robert Basset of Normanton, and it would appear that he inherited on the death of James. In 1390, lands in Weston and Normanton are recorded as held by William de Basset as of his manor of Fledborough, and in 1412 ‘Thomas de Basset’ gave to Sir Richard Stanhope and Hugh Seme ‘my manor of Fledborough with the advowson of the church of the same vill with all its appurtances and also all my tenements and lands in Sternethorp, Normanton, Stokum, Drayton, Dunham, Sutton and Marnham in co. Notyngham, together with all other my tenements and lands in Newhall Barneangyll and Wilmyncote in co. Warwick, to them their heirs and assigns’. This grant is likely to have been to trustees for the purpose of a settlement, because in 1428 a list of fees records Thomas Basset paying the feudal dues on three knights’ fees in Fledborough etc. and on a half-fee in Stokum. In the 1428 subsidy of Henry VI Fledborough's taxation had not changed since the 1291 valuation as the subsidy (10%) is recorded as 26s. 8d.

William Basset, Esq. is noted as the son and heir of Thomas Basset in 1431, and he married Katherine, a daughter of Sir Richard Stanhope. However he must have died shortly after because she is recorded as a widow in 1432 and the following year Sir Richard executed a deed declaring that after his death the manor of Fledborough and lands in Nottinghamshire and Warwickshire which he had recently been given by Thomas Basset should go to his daughter for life. It is questionable whether he was entitled to make such an arrangement, but its effect was to leave Katherine in charge of the estates, which eventually descended to her son Thomas Basset in 1477-8, when he was 34.

Thomas Basset married Margery, and had three sons, the eldest, Richard, being styled as ‘Sir Richard Basset’ and ‘Richard Basset, knight’ by Thoroton. Sir Richard married Elizabeth, a daughter of John Dunham. He made his will in 1525, desiring to be buried in the church near the Easter sepulchre, and ordering that ‘a Priest sing for my saull. My Fader, my Moder, Sir John Lisury’s saull and al my freendes saulls’. He left £6 13s towards ‘the Rood making’. In 1535 his widow Elizabeth willed to be buried in the same place ‘before Sainte Gregorie’ and left to their son a chalice, vestment, altar clothes, super-altar and all things belonging to the altar, with the ‘holye watter falte’.

The rectory of Fledborough was valued as follows in 1543:

‘Robert Trafford from there having a Mansion with the Appurtenances of the yearly value of 11s 6d, Glebe Lands Meadow & Closes £1 6s 8d, Corn & Hay £4, wool & lamb 13s 4d, Tythes & Offerings at Easter £1 13s 4d, the Offering Days 4s 8d, Tythe Pigg, Geese & other small Tythes by Estimation 3s 4d, & Tythes of certain Closes £1 6s 8d, summa valoris £10, whereof paid to the Archbishop of York for Synages 5s, and to the Archdeacon for Procurations 7s 6d, & so remaineth clear £9 7s 6d’.

This valuation would have made Fledborough a relatively rich living by local standards.

The son of Richard and Elizabeth Basset, John, married Agnes, the daughter of Thomas, lord Burgh. John Basset died in 1545, leaving a twelve year old son, Edward, as his heir. Thoroton records that he held the manors of Fledborough, Skegby and Normanton, Saxelby (Lincolnshire) and Adlingfleet (East Yorkshire), as well as land in Fledborough, Normanton, Woodcotes, Stokeham, Staythorpe, East Drayton, North and South Clifton, Ragnall, Darleton, Wellow and Grimston. Edward Basset died in 1580. He was succeeded by his son John who, in the words of Thoroton, ‘after he had sold all the rest, sold Fledborough to the feoffees of the then earl of Shrewsbury in the beginning of king James his reign, since when this goodly manor came to the possession of Robert earl of Kingston…’. The manor and advowson of the church fetched the sum of £3,750, and remained in the possession of the Pierrepont family, as represented by the Earls Manvers, into the mid-20th century. Thoroton notes that Woodcotes ‘became the Inheritance of Rutland Molyneux, a younger Grandchild of Sir Edmund Molyneux the Judge’.

In 1587 the churchwardens presented that: 'Our parson is aged and not able to serve the cure, so we want a sufficient curate'. In 1598 they reported: 'the lead of the church is blown up with the last wind, but we have spoken to a plumber to mend it again presently'.

In 1603 both the rector and churchwardens submitted that:

'1. our minister is a preacher and was a student in the University for almost four years; 2. he has only one benefice, valued at £9 9s 9d in the King's Books; 3. nothing to say [in answer to the question ' For those clergy who have more than one benefice, how far distant is each benefice from the other?']; 4. we have ten people in our parish who, since their coming to the town last March have neither come to the church nor received the communion, four men and six women; 5. there are 71 communicants and 33 non-communicants who are under 16 years old'.

In 1639 there were evidently a few problems with the fabric of the church, the churchwarden presenting that: 'the insufficiency of the seats in their parish church which have been a long time 'in doing' and are not yet finished, and so the floor is not yet paved either; the chancel is out of repair in lead, glass, and the pavement and the revestrie house is ruinous and turned into a dovecote; the parsonage house and fences towards the churchyard are out of repair in the default of James Clayton, clerk, parson there'.

In 1645 the then vicar, Edward Henshaw, wrote an account of the rectory, glebe lands and tithes appertaining to Fledborough. As well as noting the tithes pertaining to domestic animals, and noting that the living was entitled to cattle and sheep gates on the Holme, the terrier describes the rectory and glebe lands in some detail, as follows:

‘The Parsonage house consisting of three bays of building and one barne being two bays the Parsonage house yard by estimation one acre of ground be it more or less. Then one close called the vineyard containing by estimation one acre & an halfe be it more or less. Then one close called the towne end close by estimation 5 acres be they more or less. Then one little piece of ground lyeing all along under ye parsonage house wall to the north pasture … being one rood more or less. Then in the croft yt is west from Fledburgh Lane two half acres lyeing east & west being the second and third lands from the hedge on the south side. Then in Rothwell’s farm a wong called ye parsons wong containing 15 lands lyeing north & south having an headland at ye south end of them all which out the headland are Glebe. Then in ye neather…two halfe acres lyeing north and south having an hedge on ye east, butting on Butcher closes on ye north & south, somewhat further then ye south west corner of withy(?) close. Then in the Sheep walkes nine lands together by estimation three acres lying north & south butting north on westings gate having an hedge running north & south standing on them near the midst of them. Then in a close next the sheepwalk westward three rood lands lyeing north & south having a broad land belonging to Brooms Farme lyeing next them on the west. Then in the South part of upper Westings one half acre lyeing east and west in the east furlong being the tenth land from the hedge by Fledburgh outgang. Then in the same furlong two half acre lands lyeing east & west being next on the south side of ye hedge that runs east & west through the midst of westings. Then in the North part of westings one half acre with the hedge balk lyeing north & south butting north on Ragenhall outgang having the hedge of Butcher close on ye east. Then in south Part of lower westings 4 short leas with the hedge balk lyeing east & west having Woodcoates Lane hedge on ye south side of them. Then in ye close next Woodcoates Lane end called High Crosse furlong two half acres lyeing east & west they are ye 7th & the 8th lands from ye outgang on the North. Then in ye Sheep Close furlong three rood lands lyeing north & south butting on Marnham outgang south & are five lands from the hedge in ye west. Then in the same furlong three other rood lands lyeing east & west having a balke on the north side of them whch is four lands from ye house in that field….’

From the above, it is clear that the church’s lands comprised a mixture of small closes, and strips (lands) lying in the village’s open fields. Even if, in the high medieval period, Fledborough had simply possessed three large open fields, they appear by the mid-17th century to have been much subdivided and partially enclosed with what by that date must have been well-established hedges. If place names are any indication, it would appear that sheep rearing was or had been an important element in the agricultural economy of the parish.

Fledborough and Woodcotes were recorded as one in the Hearth Tax returns of 1674, when 25 dwellings were assessed for tax, of which three were exempted due to poverty. This number of dwellings indicates a population in the region of 105, hardly bigger than in the late Saxon/early Norman period. Given that Woodcotes is unlikely to have been established until later in the medieval period, this figure is likely to indicate that Fledborough itself was smaller by the late 17th century than it had been at Domesday. The settlement may have been badly hit by the Black Death or by later outbreaks of plague. A movement from arable to sheep grazing may also have contributed to depopulation, and the constant flooding from which the area suffered, would also have hindered the settlement’s development.

The Hearth Tax return for Fledborough show that the proportion of the population living in poverty appears to have been low by the standards of the time, reflecting the agricultural wealth of the Trent valley, and also the relatively high proportion of yeoman farmers in this small agricultural community:

Hearth |

Social status |

Dwelling numbers |

Percentage of housing stock |

||

1 |

Labourers & poorer husbandsmen |

8 |

32% |

||

2-3 |

Craftsmen, tradesmen & yeomen |

12 |

48% |

||

4-7 |

Wealthier yeomen etc |

5 |

20% |

||

8+ |

Gentry & nobility |

- |

- |

The vicar, listed as Phillip Squier in the Hearth Tax return, occupied a 4-hearth house, which indicates his social position as one of the higher-status residents of the village. His house is consistent with the 3-bay house described in the terrier of 1645. The others wealthy residents were Thomas Addy and Mr Milner in 6-hearth houses, and Mr Mollineux, referred to above, in a 4-hearth house, presumably at Woodcotes. There was also a 5-hearth house unoccupied at the time of the returns – this may have been Fledborough Hall. In addition to Messrs Squier, Addy, Milner and Mollineux, Messrs Nevill and Ballard, and Thomas Goodwin, John Atkinson, John Talbott, John Giles, Thomas Hunt, John Gibb, Thomas Tayler, Richard Sudbury, Peter Killiner, Thomas Hearring, Nathanial Billiatte, William Nicholson, George Porter, John Scanlen and John Gunter are also listed in the returns.

The Compton census returns of 1676 paint a similar picture to the Hearth Tax, in terms of population. In answer to the questions regarding the number of people of an age to receive communion, and the number of recusants and dissenters, the rector of Fledborough replied as follows:

‘These are to certifie to whome it may concerne that in answer to the queries proposed to the Clergie –

Primo within this p’ish of fledburgh abovesaid we have about the number of forty communicants

2do we have within this p’ish only 3 popish recusants which are all excommunicate & not any other Dissenters

April 21st 1676 Philip Squire Rector’

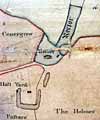

Map of 1690 Map of 1690 |

A map of 1690, drawn by Thomas Cleer for the Earl of Kingston, shows Fledborough church and rectory, along with that part of Fledborough which belonged to the Earl – mainly the southern and western part of the village, but excluding Woodcoates. The church is shown with a pitched-roofed nave and a substantial tower, but no chancel is shown and the fenestration is inaccurate, suggesting that only a diagrammatic representation is intended. The rectory is shown to the north-east, again shown in diagrammatic form. The churchyard and rectory grounds appear to be contiguous with no boundary between them. The Holmes Meadow is shown between the church and the river, and the remains of the moat which must have surrounded the Lisures’ and Basset’s manor house is clearly visible, along with a fishpond, although the Hall itself is not depicted. The lands of the parish are shown as a series of fields with mainly rectilinear boundaries, varying in size between 6 and 38 acres. Most are named as ‘pasture’ indicating animal husbandry rather than arable. The Earl’s landholding had, therefore, been enclosed by this date, which was unusual for the area; all the neighbouring parishes remaining largely in open field cultivation until the late 18th or early 19th centuries. A farmstead is shown where Top Farm is now located, and other farms and cottages are shown along Church Lane. Church Lane is shown, but the Ragnall to Grassthorpe road is not depicted, indicating that it was at best, a mere track at this date.

In 1712, on the death of the Revd P. Squire, William Sweetapple (to use the modern spelling) was appointed rector of Fledborough. The son of John Sweetapple, described in the Alumni Oxonienses as a gentleman of London, William had taken a BA in 1709 and an MA in 1711.

Given Fledborough’s small population, it is not surprising that it was 1715 before the new rector performed his first marriages. Two more marriages took place in 1717, and then in 1721 Sweetapple’s own marriage, to Elizabeth Chapman, took place. Between his marriage and his death in 1755, the Revd William Sweetapple performed a further 8 marriages for which the banns had been called conventionally in church, but during this period he also solemnised an astounding 488 marriages by means of licences which he had issued himself, having been empowered by the bishop to issue surrogate ecclesiastical marriage licences in 1728. To quote Frank West, the Archdeacon of Newark, writing in 1950, ‘gradually it became known that in this snug little hamlet on the banks of the Trent, an ideal spot for a clandestine marriage, there was an obliging parson who would grant a licence without asking awkward questions at the rectory one moment, and perform the marriage ceremony in the church at the bottom of his garden ten minutes later…From Bawtry to Bingham and from Mansfield to Newark, every apprentice who was plotting to run away with his master’s daughter, every reckless young scapegrace who had persuaded an heiress to elope with him knew that he would find a willing accomplice in the…rascally Mr Sweetapple’.

Outhwaite’s more detailed research shows the truth to have been somewhat more prosaic. It is true that several spouses came from considerable distances to marry in Fledborough, such as William Belyeat from the Isle of Ely; Robert Slainey, a widowed brick-maker, from Bolsover; Francis Spencer, a joiner, from York, Lydia Style from Buckinghamshire and Anne Calvert from Doncaster. However, these were the exceptions. 33% of grooms and 38% of brides came from within five miles of Fledborough, and only 4% of grooms and 3% of brides originated from more than twenty miles distant. The average ages at which the licensees married was also fairly typical for the period, being 26 for men and 24 for women, so it was not the case that only young people were flocking to Fledborough. There were also relatively few of the gentry, and at the opposite end of the social spectrum, few labouring people – the majority of Sweetapple’s clients appear to have been relatively local, middling farmers, tradesmen and craftsmen. Interestingly, there were 4 mariners, 2 ferrymen, a bargeman, a waterman, and a sea-captain, pointing to Fledborough’s location near the River Trent.

The marriages solemnised by Sweetapple were ‘clandestine’ in the strictest sense of the word, in that they probably breached aspects of matrimonial law, particularly the canon which stated that either the husband or wife should live in the parish where the wedding took place. The marriages Sweetapple performed by licence infringed these rules, but the ecclesiastical authorities must have turned a ‘blind eye’ to his activities and he was never accused of malpractice.

The reason so many people went to the considerable trouble of marrying at Fledborough remains an enigma. Sweetapple may have had a reputation for being more accommodating, or he may have charged less for the licence. But Outhwaite concludes that ‘it may also be the case that the chief attraction was Fledborough’s relative isolation: it was off the beaten track. If privacy was the quality licence seekers most desired, then this lowly populated Trent-side parish could certainly offer it’. And one cannot be sure how Sweetapple himself benefited. He died a relatively wealthy man, although it is possible that his wealth was inherited. He appears to have extended the rectory as described below, and in his will left £500 and silver to his daughter Elizabeth, £200 and more silver to his daughter Caroline, silver to his son John, land to his son Edward, and smaller monetary gifts to a son-in-law and a grand-daughter.

As noted from the map of 1690, the churchyard at Fledborough was contiguous with the rectory grounds, and it is perhaps because of this circumstance that a dispute between the rector and his churchwardens appears to have taken place during Sweetapple’s incumbency. In 1731 the churchwarden wrote as follows:

‘To the Revd and Worshipful archdeacon of Nottingham or his official

I Thomas Brooks the Churchwarden of Fledbrough in the Archdeaconry aforesaid do humbly certify that I have not complied with the order of the 29th of October last because the Gate by the said order directed to be repair’d at the Carriageway in the said order said to be the Carriageway leading into the Church Yard, hath been from time immemorial repaired and still ought to be repaired by the Rector of the said Parish and that the said Carriage Gate connects first with the Parsonage Yard there. And I do assure your Worship that I do not refuse to repair the same Gate out of any obstinacy, or for any other reasons than those above mentioned; and that I am ready to make proof by witness of the several Facts above certified.

And I do further certify that I have applied to the Revd Mr Sweetapple ye present Rector to join with me in this Certificate and he hath refused so to do. Given under my hand the 2nd Day of November 1731. Thomas Brookes’

The first terrier carried out by the Revd W. Sweetapple was in 1714, when he noted that the rectory comprised 3 bays, as it had in 1645. However, by 1726 he had extended it to comprise 4 bays and it was described as a 4-bay house in the terrier of 1748.

Responding to Archbishop Herring’s questions in 1743, Sweetapple stated that he had ‘been constantly Resident upon [his] living in the Parsonage House which [he] built upwards of thirty one years’. There were 11 families in the parish, all of whom attended church ‘except one of the Romish perswasion consisting of a Widdow one Son & two Daughters’. There was no school in the parish and ‘no Alms House nor any Poor Person’.

Sweetapple died in 1755, the year after the surrogate power to issue ecclesiastical marriage licences had been withdrawn. He and his wife are buried in the church.

He was succeeded by the somewhat less colourful the Revd John Richardson, who is also buried in the church, along with his infant son. The terrier of 1781 noted ‘a brick Parsonage House, built at two different periods, the old part covered with Thatch and containeth four Rooms, the lower Floors whereof are brick, the Chambers plaster; the newer Part covered with Tiles and contains six Rooms two of which are floored with Boards the other with Brick or plaster’.

Responding to Archbishop Drummond’s questions in 1764, the Richardson stated that there were 8 families in Fledborough and 2 at Woodcoats, with no Roman Catholics or Dissenters. There was no school, and he stated rather feelingly that ‘we have no alms house, hospital or other charitable endowment, no lands or tenements left for the repair of our church, or any other pious use’ (Richardson was somewhat mistaken here, in that a terrier of 1864 refers to ‘1 silver almsdish with inscription ‘This plate and £5 for the use of the poor of the Parish of Fledbro’ was given by Elizth widow of John Rayson 1744’. John Rayson is recorded as a churchwarden in a document of 1731. The lack of resources was a pressing issue, for it was in the same year that the rector petitioned to reduce the size of the chancel and demolish the chantry chapel, as described more fully in the following section, stating that it was ‘much out of repair by the violence of the late high winds…and cannot be repaired but with great difficulty and expense.’

Chapman's map Chapman's mapof 1774 |

Chapman’s map of 1774 is the earliest depiction of the entire parish. Although insufficiently detailed to show individual dwellings within the settlement, it shows the pattern of settlement, along both sides of Fledborough Lane, with a subsidiary hamlet at Woodcoates, and the Ragnall to Grassthorpe road is shown, although it appears to pass through open fields south of its junction with Fledborough Lane.

The Revd John Richardson was succeeded in 1779 by the Revd John Charter, and then in 1784 by the Revd John Penrose. Writing in 1790, Throsby states of Fledborough that ‘here are only seven or eight houses…The church, which is a little ordinary place of worship, is dedicated to St. Gregory.’.

1792 map 1792 map |

A map of 1792 shows Fledborough in detail, and the reduced chancel of the church is evident. Including the rectory but excluding Woodcoates and Fledborough Farm, which had been recently built, there would have been only eight dwellings at the end of the 18th century. Fledborough’s population stood at 71 in 1801, indicating continued stagnation.

The 1792 map shows the Ragnall to Grassthorpe road and the recently constructed Fledborough Farm, and it shows the land within the parish north of Fledborough Lane, as a series of enclosed fields between 4 and 24 acres in size. A number of the field names shown on this and the 1690 map are of interest. Rushy Close and The Marsh Meadow indicate poorly drained land, while Sugar Park suggests fertile, productive soils. North and South Conegrew may allude to rabbit warrens or conigers established in the medieval period, perhaps by the Lisures family. Upper and Lower Sheepwalk Pasture and Tup Close suggest that sheep farming was or had been important locally, and Hopyard and Pease Bloom Close indicate land on which hops and peas were grown. Peas had been a staple of open field crop rotations, improving soil fertility and producing food and bedding for both humans and stock, and they remained an important crop until the modern period. Great and Little Brick Kiln Close are also of interest, indicating where bricks were made, and perhaps suggesting the conversion from timber, wattle and daub houses to brick-walled structures which took place during the late 17th and 18th centuries.

The Revd John The Revd JohnPenrose |

Although the Revd John Penrose had accepted the living in 1783 or 1784, it was serviced by the Revd Wootton of Tuxford until 1800. Penrose visited in mid-May, and writing to his wife, he said:

‘Fledborough was not looking to advantage, the season being more backward in the clays…The House has three poor families in it, and the plaster, etc is much out of repair. Owing to embankments further down the river it is more subject to floods than formerly, and I had no conception of such a road as led to it from the turnpike [the Markham Moor to Dunham road, now the A57]. I went in the gig, and how I got Mercury [the horse] and it through I cannot tell…I fear it would be putting all our lives in jeopardy to inhabit a house so often flooded and that must, of course, long retain the damp.’

Despite his reservations, the Penroses moved in a year later. Mrs Penrose wrote on 13 May 1801 to say that ‘we are even more comfortable than we had a right to expect, and that we find all our parishioners friendly and agreeable…Vulgarity even among the lowest we have not met with…[our daughters] profess themselves enchanted with the rich scenery around us; and indeed at this beautiful season of the year I have many times compared it in my own mind with the garden of Eden.’ Soon after moving in, they began building, and by 28 October Mrs Penrose wrote saying that they able to drink tea in their new dining room. However the Terrier of 1809 lists the same number of rooms as that of 1781, implying that the Penroses renovated and remodelled the parsonage, rather than actually rebuilding.

At about the same time, Penrose officiated at his first funeral. Writing to his sister, he described it thus:

‘…we have lost one of our principal parishioners. It seems to be the custom here for the Clergyman to attend at the funeral house…I went there between 3 and 4 o’clock in the afternoon and made one of the procession to Church. The procession was a most curious one. The corpse was carried in the Farm Waggon and the principal mourners rode in the muck-cart, neither of which appeared to have been washed since last Winter’s mud. The family however were dressed in the handsomest mourning and the Rector had hat band and gloves. Funerals here are so rare that they hardly know the ceremonials of them. There were no stools to set the corpse on either at the entrance of the Churchyard or at the Church, nor ropes to let the coffin down into the grave. Our little girls’ work stools were borrowed to supply the former deficiency, and the napkins made use of for the latter. I should have told you that an undertaker attended with a handsome black velvet pall trimmed with white satin. The next morning, gloves were sent round to all the matrons in the Parish, and diet cakes. Such is the established usage’.

It is interesting to note that when the Penroses’ fourth daughter, Margaret, died in 1812, the local customs were followed. All the bearers were of the servant class and were female. ‘…they had white muslin shawls, ribbons and gloves, our two servants mourning, Mr Browne [the officiating clergyman] scarf and hatband. After all was over we sent about the customary cakes, etc., and gloves to all the Bretts, Mr Minnitt’s, Mrs Billyards, Miss Ransom, Miss Sampson, Mrs Crawley and Waddingtons and the men who assisted. Mr Eyre a hatband and gloves…’

The chancel The chancelbefore 1890 |

Engraving of the Engraving of the church in the early 19th century |

Fledborough suffered a hurricane in 1802, which blew in windows, knocked down chimneys and ripped 2 tons of lead off the chancel roof, carrying it more than 36 feet in one piece. Lydia Penrose, the vicar’s third daughter, made several sketches in and around Fledborough, one of which shows the chancel as it was in those days, that is after it had been shortened but before it was replaced in 1890. The royal arms shown in the chancel are now located above the tower arch, and the east window depicted in Miss Penrose’s sketch is now located in the south wall of the Victorian chancel. Decalogue boards, showing the Ten Commandments and possibly The Creed, are depicted either side of the east window. Another sketch shows the exterior of the church, again showing the shortened chancel. The original porch is depicted, and there is no evidence of buttressing to the south aisle.

The Penrose letters make it clear that the Trent was a major highway at the time, not only for coal, timber and other goods, but for people. Steam packets ran regularly between Hull, Gainsborough and Nottingham, and were often used by the Penroses in preference to the coach, as they took them on board and landed them almost at their door. They had connections at Thorney, where the Revd J. Penrose accepted a curacy in 1802. The village lies on the eastern side of the Trent, and if the vicar was visiting on horseback he would use either the ferry at Dunham or that at Marnham. If the family was going on foot, which they appear to have done regularly, carrying indoor shoes with them, a servant would row them over from Fledborough and fetch them later.

The flood of 1811 The flood of 1811 |

However, the Trent was more of a menace than a benefit, flooding its adjoining parishes with what must have seemed to be monotonous frequency. The floods of 1795 were ‘held in awful remembrance’ according to Lydia Penrose, and the house was cut off in 1806 and 1811. The floodwaters rose to about their 1795 level in October 1824 when ‘the waves just touched the corner of the north-eastern buttress of the Chancel. The water got into the Parsonage Kitchen on the 13th, and the parlours on the 14th, when it was 11 inches deep in the dining room’. A sketch of hers survives, showing the extended parsonage amidst floodwater during 1811 when it appears not to have risen high enough to enter the house.

Penrose died in 1829, and he and his wife are buried in the church. He is chiefly remembered for the fact that his youngest daughter Mary became the wife of Thomas Arnold, who as headmaster of Rugby School from 1828 until 1841, had a profound influence on the development of the country’s educational system. Their eldest son Matthew was also famous as a poet and man of letters.

A map of 1831 shows that almost the entire village was liable to flooding, including the church and rectory, and it depicts proposals for an embankment along the western bank of the River Trent, a drain along the northern parish boundary, and a series of sluices, which it was hoped would prevent future inundation. Sanderson’s map of 1835 shows that the drain had been built by that date, and that a shuttle, or sluice, had been constructed on the arm of water immediately to the east of the church. The embankment along the western bank of the river had been constructed by 1844.

The 1831 census for Fledborough gives details of occupation, for men over the age of 20, as follows:

Occupational categories |

Percentage employed |

Number employed

|

Landowners & Professionals |

9% |

2 |

Farmers employing labourers |

30% |

7 |

Farmers without labourers |

- |

- |

Agricultural labourers |

48% |

11 |

Non-Agricultural labourers |

- |

- |

Manufacturing |

- |

- |

Retail & Handicrafts |

- |

- |

Servants |

13% |

3 |

This confirms the overwhelmingly agricultural character of the parish, and although direct comparisons with the 1674 Hearth Tax data cannot be made, there is perhaps an indication that small yeoman farmers had declined into agricultural labourers during the intervening period.

Tithe map (1839) Tithe map (1839) |

The Tithe Map of 1839 shows the church, with a drive from the churchyard leading to the rectory and its outbuildings, described as ‘church and churchyard, rectory house, out offices, yards, gardens and orchards’. It is recorded under the Revd Augustus Otway Fitzgerald, who had been installed in 1829. The Hall is shown with outbuildings, yards and a considerable garden, north of the remains of the moat. It is noted in the Tithe Award as belonging to Earl Manvers, and occupied by John Charles Picking. The arm of the river, with the sluice described above, is depicted to the east of the Hall and the rectory.

A religious census was carried out in 1851. By this time the village’s population had grown to 130, which is the highest it ever achieved. The census recorded that the church had an average congregation of 30, with slightly more (33) attending the morning than the afternoon services (28). There were also five attendees at Sunday School. Watts calculates that one third of those who attended the less popular service would not have attended the other, and thus it can be estimated that 57 of Fledborough’s inhabitants went to church, i.e. 43% of the population. By the mid-19th century, only about 40% of the population attended church, but the figure was about 44% in small villages, so Fledborough’s attendance was typical the standards of the day.

Despite the defences which had been built in the 1830s and 1840s, the Trent flooded disastrously in November 1852, as described by Mrs Fitzgerald, the rector’s wife. Her account is so vivid, both in terms of the drama of the flood and the day-to-day life of the village, that it is quoted at some length:

‘On Friday, 12th November, the Trent began to overflow and the cattle were taken out of the Holme which was covered with water before night. [On] Sunday…after morning service our manservant George Green came running to us as we walked home from Church, to say that the water had risen so rapidly since we went into Church that there would only just be time to put down the flood gates at the entrance of the holme towards the lane. This was accordingly done as quickly as possible and every crevice dammed up…we read in the Times that the Soar which empties itself into the Trent had risen 14 feet…and as we knew that this vast body in addition to that already brimming over the river banks, must sooner or later pour down upon us, we began to be alarmed.

We went to Church as usual in the afternoon, and on coming out walked to look at the progress of the water from the garden wall. It had by this time reached to foot and was actually dripping a little through a part of the wall where a join had been made, and before dark a pool began to appear in the hollow below the flower garden, the water being forced through the bank by the enormous pressure. The water continuing to rise, our fears increased, and as soon as dinner was over we moved all the furniture from the three front rooms upstairs, with everything else which we thought might spoil. This was accomplished between 7 and 8 o’clock. [The water] was then stationary until about half past eleven when it began to rise again assisted by the tide. No one in the house save the children had their clothes off during the whole of that fearful night. The rain was incessant, the night dark and…it made one’s heart sink to hear every half hour “still rising, Sir” especially as we were told that the wall (now our sole barrier) shewed symptoms of leaking and was not considered safe. Still we hoped on…Several feet of the wall gave way suddenly and fell in a mass within a few feet of the house, and the pent up water rushed in like a waterfall, on Monday about 7 o’clock. I was at the nursery window and saw the crash. The maids ran upstairs screaming with terror. I begged them to snatch up the children, who were partly dressed, to wrap round them whatever warm things they could first find and to follow me. In a few moments we were all at the front door, where Augustus met us…a minute afterwards we were joined by the Greens, who were making their way through the holly hedge up the garden, George with his two eldest children in his arms, his wife and servant girl each with a babe behind, these poor children torn from their beds with no other covering than their night clothes.

It was like an Irish flitting and I could hardly help smiling as I looked on the scene. I was in my night cap and dressing gown, Mrs Green but half dressed. We were going to take refuge in the Church when we were hailed by our kind neighbour, Mrs Pickin, who begged us to come to her house opposite, which we did with thankful hearts. Fortunately the ground falls suddenly at the spot where the wall broke, the water therefore rushed past the back of our house by this descent passing through George Green’s cottage which adjoined our stables and made an exit for itself by breaking twenty or thirty feet of a new bank lately made behind the stables to protect us from the back water. It then rolled on three feet deep about a mile into Dunham, breaking another bank on its road…happily all the animals were saved excepting two of the children’s rabbits, though the pigs were swimming and were got out with difficulty. The calves which were at first put into a shed in Conygree were obliged to be removed again as no one could have got to them after a short time. Our horses were at one farm, the sheep and cows at another and so on. Nothing could exceed the kindness and attention of each and every one of our parishioners of every class and degree, vying with each other to be of use to us.

The cottages occupied by Wheat, Wright and Woodhead were also flooded, their inmates being obliged to live upstairs, the water having made its way in that direction as far as the steps of Mr Howard’s house, his stackyard was under water. Thus in a few short hours, the whole face of the country as far as the eye could reach was converted into one vast waste of waters, stretching away for miles and miles, by the Trent side in this place as far as a mile inland, beyond the guide post to ‘Fledbro’ only’, relieved only here and there by the speck of a church, a house or a few trees, every boundary such as hedges etc. being entirely effaced while here and there a few yards of ground appeared which chanced to be somewhat higher than the surrounding level…’

It was the 4 December before the water level fell sufficiently for services to take place in the Church. The Fitzgeralds could not return to the Rectory until five weeks after it had been flooded, and even then could only occupy the upstairs rooms ‘the damp state of everything can be imagined’.

Plan for rebuilding Plan for rebuilding the chancel (1857) |

Plan of 1868 Plan of 1868 |

The Revd Charles Neville took over from Augustus Fitzgerald shortly after the 1852 floods, and by 1857 he had commissioned the well-respected architect, J L Pearson (1817-1897) to provide a design for replacing the truncated chancel of the church. Pearson’s designs were not implemented, and a plan of 1868, drawn to clarify the extent of the churchyard in relation to the rectory grounds, shows the shortened chancel which had been in existence since the 1760s.

A terrier of 1864 describes the rectory, the church fittings and, unusually, the church itself, again confirming that Pearson’s scheme had not been carried out:

‘…The rectory house built of brick and slated containing three Sitting Rooms with entrance, Kitchens, Pantry, dairy and other offices, nine bed rooms and two attics with brick and tiled wash house attached and other offices adjoining, also a block of buildings containing a Cottage of five rooms stable loose box and carriage house &c with large laundry and chamber for hay fruit &c near which are tool house pig sties and other small out buildings all in good repair…

Belonging to the said Parish are the Parish Church consisting of Tower rather more than 18 feet square (internal measurement as are those which follow) Nave 48 feet by 18·3 N and S Aisle each same length as Nave & respectively 10·2 and 12·9 wide. Chancel reduced to 14·5 by 18·8 from an ancient chancel 44 feet long having a S Aisle of 22ft and a vestry or other building on the North. A Font and Pulpit of stone a moveable reading desk and seats in the Nave and part of the Aisles two bells a Communion table…’

The Revd C. Neville left the parish in 1877, and was succeeded by the Revd George Kershaw. At a vestry meeting of 27 March 1889 a resolution was carried ‘that a faculty be applied for in order to carry out the rearrangement of the Chancel as shown in the Plan submitted to the meeting as far as the Chancel Arch, the pulpit, lectern and reading desk to be within that space, but the choir seats are to be provided and placed in the Nave’. The work was done in 1890, and appears to have comprised a simplified and reduced version of Pearson’s 1857 design. According to White’s Directory of 1894 ‘At the same time new altar rails, reredos of oak, and stone pulpit were erected; the east window is new, the old one being removed to the south wall of the chancel; the broken panels of an Easter sepulchre were inserted in the north aisle, and the floor of the chancel retiled; the whole of the cost amounting to about £650. The reredos was the gift of the present rector’.

W T Arnold, a great-grandson of the Revd John Penrose, visited Fledborough in April 1896, and his account, sent to his aunt, a grand-daughter of the Revd J. Penrose, gives a real sense of what the village must have been like at that time. As such, it is quoted at some length:

‘We took the train to Retford on the Great Northern, and then rode the seven miles southwards along the Great Road to Tuxford…after lunching at Tuxford, interesting as the place where anyone bound for Fledborough in the old days must have left the old coach road to plunge into the wilds, we set out due east. Four miles or so of a very lonely country road, or rather lane, with endless masses of primroses in the hedge banks, brought us to a three lanes end, and on one arm of the decrepit sign post was ‘To Fledborough only’…after another mile [we] saw the low steeple of Fledborough, dismounted at the gate, and walked up the drive (as you know Church and Rectory are all in one place so to speak) which was lined with splendid wallflowers…looked into the open Church for a few minutes, and then to the rectory door…Mr Kershaw made his appearance and kindly welcomed us – a fresh-coloured, pleasant man, and a gentleman.

He is a widower, and there is only one child at home – a Repton schoolboy. He was just finishing some letters for the post, so we begged him to go on, while we went out to the Holm and down to the Trent. It was very pleasant and sunshiny and restful, and the broad Trent with two fishing smacks moored hard by, quite imposing….But as one looked southwards there was a mighty change. The new East and West Railway starting from Chesterfield to a point on the Lincolnshire coast, goes right through Fledborough, and we had been following its course all the way from Tuxford.

It is being carried over the Trent meadows by a great viaduct of many arches as yet unfinished, and as one looks from the drawing-room windows of the Rectory, these great arches, by no means ugly happily, are the conspicuous object in the distance, perhaps a mile away. There will be a Fledborough station, so that ‘Fledborough only’ will be a thing of the past. By the way Mr Kershaw told us that the original form of the signpost was still better: ‘Fledborough and no further’ and that it was his predecessor, Mr Nevile, who had put up the ‘Fledborough only’ some thirty years ago.

‘…we did the Church thoroughly under his guidance, including of course your tiled floor, with the marble slab and inscription in the middle, and the plain stone inscribed ‘John Penrose’ and the little brass to him…Then Mr Kershaw gave us tea. And we parted great friends, after a most successful little visit, which had not one unpleasant touch in it, as these attempts to give form and substance to a mind-picture, formed from reading and listening, so often have.’

Map of 1900 Map of 1900 |

The new chancel, somewhat longer than that which it had replaced, is depicted on the Second Edition Ordnance Survey 25ʺ map of 1900. In that year, the Revd G. Kershaw was succeeded by the Revd Charles Cadogan Campbell. At a vestry meeting of 20th April 1911 ‘the subject of the repair of the exterior of the church was discussed and the Rector said he would write to Mr Wordsworth about it’. It seems likely that the Mr Wordsworth referred to here, was R W Wordsworth, land agent for Earl Manvers of Thoresby between 1883 and 1914, because the porch was rebuilt, buttresses added and general repairs made shortly after and on 2nd April 1912 the vestry meeting recorded that ‘a resolution was passed that a hearty vote of thanks be given to Earl Manvers for his kindness and generosity in restoring the church and the Rector promised to communicate this to his Lordship’.

Archbishop Hoskyns visited Tuxford deanery in January and February 1914, and in his letter to the clergy he made the following points, many of which became still more relevant as the 20th century progressed:

‘This Deanery is in population one of the smallest in the Diocese. Only one parish, Tuxford, has a population of over 1,000, while six are under 200…

The people in this area are engaged nearly entirely in agriculture. For the most part the farmers work the farms with very few labourers, with the result that the young people leave the villages for towns or the colonies…

The difficulties surrounding Church work in such Parishes are obvious. They arise from the extreme loneliness and too often poverty of the Clergy. To obviate the former difficulty there is the proposal to unite many more of the Parishes. In three cases this has been done. On paper such a solution appears simple, but great difficulties arise in the practical working. However, with the assistance of well-trained Lay Readers some of these difficulties may be overcome.

Another serious difficulty arises from the strain thrown upon a tiny Parish in preserving the fabric of the Church building. Whilst the land was in the hands of large and generous landlords, the strain was shared with and often wholly borne by them. Today, as the larger properties are being sold, the burden falls upon a few farmers and labourers, who are quite unable to bear the cost.’

Despite the opening of Fledborough Station in 1896 the parish’s population had declined during the later 19th century to stand at 91 in 1901, and although it rose to 114 in 1931 it had dropped to 87 by 1951. By this time the rectory was let out as a private residence. It may not be entirely coincidental that by the mid-20th century, the parish’s connection with the Earls Manvers of Thoresby had been severed. The Thoresby connection has been referred to several times before, and it seems clear that the family had contributed to, or entirely paid for, many of the repairs and alterations which had taken place since Robert earl of Kingston had acquired the estate, manor and advowson in the early 17th century. In 1952 the vicar, Leonard Conway Warner, launched an appeal for £1,000 to repair the church roof, and this was reported rather poignantly in the Nottingham Guardian of 30th August:

‘Fledborough today is almost a deserted village. Little remains to remind the casual visitor of the past. He will not hear the bustle of the vanished port and sense that the now placid water was once stirred and busy with traffic. He will not listen for the forgotten sound of children’s voices on the lawn between rectory and church. The church is the one reminder that Fledborough has left. And in less than a lifetime unless £1000 can be found, and found fairly quickly, that too may be a casualty of age and forgetfulness’.

Although the funds were found for repairs, Fledborough continued to decline in population, and the station was closed to passengers in 1955, and completely ten years later. With a shrinking population and a tiny congregation, the church became unsustainable as the 20th century advanced and on 1 January 1991 it was vested in the Churches Conservation Trust.