For this church:    |

Keyworth St Mary MagdaleneChurchyard

Keyworth churchyard occupies about three-quarters of an acre and contains around 280 gravestones, most apparently still in their original positions. Of these, only 14 with legible inscriptions date from before 1800, of which all but one are from 18th century. Yet the parish registers record 667 burials between 1655 (the earliest registration to have survived) and 1799, implying that the great majority of interments during that period were not marked by a memorial stone, which was a luxury few in Keyworth could afford. Until the 19th century, the churchyard was the only cemetery in Keyworth, though a few may have buried their dead in unconsecrated ground. There is, for instance, a private family vault marked by two mid-19th century gravestones, in the garden of a farmhouse in Thorpe-in-the-Glebe, but none is known to exist in Keyworth. However, the Keyworth Congregational Church (now the URC) opened a graveyard in the early 19th century. The earliest gravestone in it is dated 1838. Also, a small Baptist chapel at the southern end of Main Street was active for a few decades after 1851. It had an adjoining graveyard on Wysall Lane, but few were buried there and it is not marked by visible gravestones today. Keyworth Methodist and Catholic churches have never had space for their own graveyard. The municipal cemetery off Wysall Lane, was opened in the 1970s.

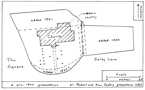

The pre-19th century churchyard, to the south and west of the church, was less than a third of its present size (see plan). Here are the older gravestones, the oldest being that of Robert Coppley and his wife Ann, who died in 1693 and 1702 respectively. It is decorated with a Belvoir Angel, trademark of a local engraver at that time. Like most of the other pre-1800 gravestones, it is made of Swithland slate, on which engravings are well preserved. It seems that the southerly bulge of the churchyard’s perimeter was increased during the rebuilding of the boundary wall in the 1820s. A more substantial extension, to the north of the church, was made in 1861, when the rector, Alfred Potter, ceded part of his rectory garden to the churchyard in exchange for land he had taken out of the rectory field two years earlier, to build his new rectory. He was buried there himself in 1878, near the gravestone of his 14 year-old son, Claud. Another stone in this part of the churchyard is that of Private Henry Marriott of the Sherwood Foresters, killed in action in 1917 and the only Keyworth wartime fatality to be brought home for burial. An annual grant from the Wargraves Commission pays for its upkeep. A final extension to the churchyard was made in 1930, when a piece of the rector’s glebe alongside Selby Lane was added. By the 1970s this had been filled and most further interments in Keyworth have taken place in the municipal cemetery off Wysall Lane. There are, however, exceptions: two church stalwarts over many decades, Gladys and John Holden, were buried in the churchyard in 1985 and 1996 respectively, as have been a few close relatives of those already buried there. Like many churchyards, Keyworth’s stands above its surroundings, particularly on the south and west, where the boundary wall holds back a surface more than six feet above the adjoining roads. This is no doubt due in part to the thousands of interments that have taken place there over the past millennium, together with rubbish taken out of the church and dumped outside at regular intervals. In Keyworth’s case, however, it may also be due to the presence of springs around the church, now dried up or drained away. The conjunction of glacial boulder clay and meltwater sand beneath the churchyard, exposed during recent repairs to the perimeter wall, would be responsible for the springs. Water would have washed material downhill as it emerged from the ground, thereby undermining the earth above and causing mini-cliffs to form - a process known as spring-sapping. When the churchyard was laid out and defined it is likely that a wall would have been built at the foot of these mini-cliffs, with the ground behind built up and levelled off. Meanwhile, the soft roads skirting the outside of the wall (only given a hard surface in the last two centuries) would be deepened by traffic ruts and soil creep downhill, away from the wall, accentuating the mini-cliff into the vertical drop now represented by the boundary wall itself. |