For this church:    |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| a. | Prebendaries | |

| b. | Medieval and Early Modern Vicars | |

| c. | Chantry Priests in the Middle Ages |

a. Prebendaries

To explain the development of Norwell, we must begin with the prebendaries of Southwell, the clergymen who exercised rights as landlords as well as patrons of the living. Many were national figures but some had considerable influence locally, not least the first identifiable Norwell prebendary, the remarkable Italian, Master Vacarius. He was a distinguished lawyer, who first taught at the University of Bologna, but then passed into the service of Archbishop Theobald of Canterbury (1138-61) before serving two successive Archbishops of York. He died around 1200.

Among other medieval prebendaries who made a particular contribution was Master John Clarell (Overhall, 1255-95). Without ever reaching the highest positions in the church, he had a distinguished career as a diplomat, lawyer and papal chaplain. But from the start of his appointment as prebendary of Overhall, Clarell took a lively and personal interest in Norwell.

He quickly turned his royal contacts to advantage by obtaining various seigneurial rights for himself and his successors in Overhall manor. These included rights of free warren, the assize of bread and ale and permission, with Henry Le Vavasseur (Palishall, 1257-80), to make a park. He also got a licence to hold a weekly market on a Thursday and an annual fair of three days at the feast of Trinity.

Clarell resided in the village and it is possible that he was responsible for digging the moat and reconstructing the manor of Overhall in stone. Certainly during his time as prebendary, several Archbishops of York not only visited the village but stayed on numerous occasions. Finally, in his will, Clarell left money for the repair or rebuilding of the chancel of the church, the documentary and archaeological evidence suggesting that it was through this benefaction that the great east window was built c1300.

It is less clear how many of the later medieval prebendaries spent time in Norwell; some had Cambridge fellowships or important clerical positions at York. Yet some did maintain reasonably close ties with Norwell. As far as the post-Reformation prebendaries were concerned, however, Norwell was largely a source of income, but they stolidly exercised their seigneurial rights. Some rents were still collected from tenants in the village in the north porch of the Minster until modern times.

The last prebendary of the old Chapter died in 1873. There was then a brief intermission, but with the establishment of the new Diocese of Southwell in 1884, the chapter was reformed, and men named to the old prebendal stalls. The nominations were, however, honorific and, although still used, few recent holders of the three Norwell prebends have had any personal contact with the parish church.

b. Medieval and Early Modern Vicars

At the time of Domesday Book (1086) Norwell had a church and a priest. It is possible that the priest was also an early prebendary of Overhall; this was certainly the case of Vacarius at the end of the twelfth century. But towards the end of his life, he arranged to give ‘half the church of Norwell’ to his nephew, Reginald. This explains how the prebend of Norwell Tertia Pars came to share with Overhall the right to appoint vicars at Norwell. From the thirteenth to the eighteenth century Norwell had two vicars.

Fairly detailed lists of those appointed to the Overhall ‘mediety’ can be established from the mid fourteenth century, and for the Tertia Pars ‘mediety’ from the late fifteenth century until the last holder, John Townsend, appointed in 1718. In the previous year he had already been presented to Overhall mediety, thus finally bringing the system of medieties to an end. After Townsend’s day a single priest held the living; since 1990, it has been held jointly with those of Caunton, Cromwell and Ossington.

c. Chantry Priests in the Middle Ages

Prebendaries and vicars were not the only clergy in medieval Norwell; there were also chantry priests for the two chantries established in the Middle Ages. The first was endowed in 1340 and dedicated to the Virgin by Robert de Wodehouse, former treasurer of England, and prebendary of Palishall (d.1346). This chantry was initially served by two chaplains.

A second chantry, also for two chaplains, existed by 1375 when the right to present to the chaplaincy passed from Nicholas Brett to Nicholas Dymok. In 1412 this chantry passed from Dymok’s descendants to Nicholas Coningston. Since this chantry is not listed in certificates of 1547-8 when chantries were suppressed, it is likely that it had long lapsed or, like St Mary’s chantry, been united with another of the Minster’s chantries in the course of the fifteenth century.

In this way, the medieval villagers of Norwell not only contributed to the maintenance of three prebendaries but also to several chantry priests, either at Norwell itself or in the Minster, until the chantries were finally abolished in 1547-8.

Part Two: The History of the Church Building

| i | Before the Reformation | |||

| ii | The Nineteenth-century Restoration | |||

| a. | Restoration of the Chancel 1857-9 | |||

| b. | Restoration of the Rest of the Church 1872-5 | |||

| iii | Work on the Church since the Restoration | |||

i. Before the Reformation

The origins of the building must be sought in the late Saxon period, but no trace of any surviving work from this early period remains. It is almost certain that the first church would have been made of wood and that Norwell, following a more general pattern, was transformed into a stone church around 1100, since the first identifiable surviving fabric seems to date from the early twelfth century when a small rectangular church, with nave and chancel, was probably built. The westernmost pillar of the north aisle appears to conserve some of this early work.

The

south door The

south door |

In the latter half of the century, probably between 1150 and 1180 (the time of Master Vacarius) a more substantial three-bayed church was started. The present south doorway is a remnant of this phase, though it may have been moved to its present position a few years later when the south aisle (its solid round pillars, with waterleaf capitals, dated stylistically 1200-25) was punched through the walls of the earliest stone church.

A similar process was carried out when the north aisle was inserted a generation later as shown by its octagonal pillars, with additional evidence of tooling c1225-1250. There is both documentary and architectural evidence for a further major refurbishment and expansion of the church around 1300.

The documentary evidence comes from the will of Mr John Clarell, prebendary of Overhall (1255-95), who left money for ‘the repair or rebuilding of the chancel’. The architectural evidence is the fine five-light traceried east window (presumably erected in part fulfilment of Clarell’s legacy), the addition of both north and south transepts, and the way in which the nave was extended by a fourth bay and a new junction with the tower contrived. The south-western end of the north aisle wraps round a pre-existing tower buttress.

Tomb recesses dating from 1280-1300 in each transept as well as aumbries from a few years later, coinciding almost exactly with the foundation of known chantries, date much of this work reasonably accurately. A fine, now free-standing, geometrical cross grave-marker in the south aisle also seems to date to this period. The pillars flanking the opening into the south transept as well as those of the tower arch, with keeling characteristic of this period, also seem to be associated with this enlargement of the church. A new porch was also added in the early fourteenth century.

The final medieval phase of the development occurred in the latter half of the fifteenth century or beginning of the sixteenth, closely coincident with the period when William Worsley, Dean of St Paul’s, was also prebendary of Overhall (1453-99). Its major aspects were the re-roofing of much of the church (apart from the north aisle). The nave was raised by the addition of a clerestory with five windows on each side.

Looking

up at the Looking

up at thenorth transept roof |

Detail

of the Detail

of the“green man” boss |

New crenellated parapets were added to the nave, the transepts and the chancel. A further storey was added to the tower, which was also given a decorated perpendicular-style parapet and gargoyles. Among the best surviving evidence for this major campaign of renovation is the fine, carved timber-roof of the north transept, with its bosses including a green man.

Stairs in the eastern-most pillar of the north aisle led to the opening to the rood screen, originally over the chancel arch. The removal of the screen hints at some of the changes which the Reformation brought to the appearance of the church. There is, however, also later evidence for a screen still in place in the chancel arch before the restoration of 1857-8, which raises the intriguing possibility that part at least of the medieval rood continued in use after the mid sixteenth century.

Whatever was the case with the screen, the dissolution of the chantries in 1547-8 would certainly have brought other changes with the removal of altars and possibly of some founders’ tombs, since neither of the effigies now surviving in the church were originally intended for the niches they currently occupy. The figures concerned, a knight in early fourteenth-century armour and a lady in mid-fourteenth-century dress, were probably members of the Lisures family who occupied the manor of Willoughby at that period. They may have come from a former, free-standing tomb, the location of which is now unknown.

ii. The Nineteenth-century Restoration

| a. | Restoration of the Chancel 1857-9 | |

| b. | Restoration of the Rest of the Church 1872-5 |

Very little structural change appears to have occurred between the mid sixteenth century and the mid nineteenth century when extensive restoration was undertaken. It is possible that some damage was inflicted during the Civil War when the neighbouring prebendal manor of Overhall to the south of the church, was briefly besieged in 1645. Thoroton (1677) refers to some armorial glass that is no longer extant but does not mention war-damage as such. It was general deterioration over time rather than violent incidents that mainly affected the church.

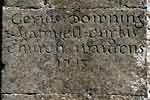

Inscription

on tower Inscription

on towerbuttress, dated 1713 |

By the early eighteenth century, for instance, it was necessary to rebuild the butresses for the tower, work undertaken in 1713 if an inscription bearing the names of the two wardens of that date is a guide. A few years later, attempts were made to improve the conditions in the church by stripping out old seats and replacing them with new pews.

This work was done in several phases: at the vestry meeting of 18 December 1724 the minister, wardens and inhabitants agreed ‘that all ye seats on ye South side of ye Middle Ile be made new and seats provided for those that want’, a measure repeated on 2 February 1726 when it was agreed that ‘the seates [on the north side of the church] to bee pull’d upp and new seates or pews to bee made and seates to bee provided for them that wants’; while on 17 January 1727 it was agreed ‘first a new reading deske to bee made, pulpitt and all the rest of the seates in the North aillon’.

But there is no evidence of major expenditure, and the reports of Ewan Christian before the restorations in the nineteenth century describe a church that was by then in very poor physical condition.

Christian, architect for the Ecclesiastical Commissioners, restored the church in two distinct phases: between 1857 and 1859 he restored the Chancel, then in 1874-5 he carried out restoration of the rest of the church. Thanks to very detailed records and correspondence surviving in the archives of the Commissioners (who had inherited in Norwell the responsibilities of the Old Chapter at Southwell in 1841), it is possible to follow the nineteenth-century restoration process at Norwell in a way, it seems, largely unrivalled amongst other Nottinghamshire churches.

These documents, relating to two building campaigns, provide information on a number of important matters relating both to the building itself and to the political and financial issues which the vicar, James Morris Maxfield, Churchwardens and Restoration Committee faced in persuading the Commissioners to carry out their statutory obligations and to assist in maintaining ‘the Mother Church of the Parish, which is a large and antient building of striking Architectural proportions and style’.

On 1 April 1856, the vicar and churchwardens presented a ‘Memorial’ to the Commissioners, drawing attention to the ‘state of progressive dilapidation and decay’ of the church ‘notwithstanding the custom of the Inhabitants, from time immemorial and year by year, of granting a rate for necessary repairs’. Whilst they admitted that the chancel, which was the property of the Commissioners was ‘not so much out of repair as some parts of the Church’, it was ‘nevertheless much dilapidated and requires to be thoroughly restored’.

They drew attention, for instance, to that fact that ‘The fine decorated chancel window is so bad as to admit of no substantial remedy short of renewal. A part was blown in a short time ago ...’. A few weeks later, on 28 May 1856, the Commissioners referred the Memorial to their architect, Ewan Christian, while their secretary wrote to the Rev James Maxfield on 31 May saying that they would use income from some of the land allotted to them in Norwell in lieu of tithes (some 330 acres of the 1900 acres they still owned in the village) to pay their share, provided other landowners also contributed at a rate to be agreed. On 16 July 1856 Christian submitted his report on the state of the chancel to the secretary.

a. Restoration of the Chancel 1857-9

Christian confirmed that the chancel was in a very poor state of repair: various fissures and fractures were identified, the gable over the window arch was in poor condition, quoins had moved, pushing buttresses out, tracery and mullions needed replacing, jambs returned to perpendicular, underpinning was advisable for the south wall, the parapet was wanting in parts, and so on.

The

chancel roof The

chancel roof |

He was particularly informative on the roof ‘which is an enriched one of the 15th century, framed of oak with moulded and curved tie beams and richly moulded ribs forming a panelled ceiling’. It was ‘not in perfect condition’, some beams and ribs were sound, but ‘the wall-plate and other of the ribs are defective, the panel boarding is wholly gone and some of the ribs are wanting’. Nevertheless he concluded, ‘The roof is capable of repair of which it stands much in need.’ On the exterior, the lead needed recasting since it was not ‘in a satisfactory condition’.

More seriously, however, although he describes the roof as ‘in itself an undoubtedly handsome one’, he had reservations about preserving it on aesthetic grounds since ‘it is not harmonious with the east window across the arch of which the tie beams cut in a very unsatisfactory manner. Externally also the parapet which follows the line of the roof has destroyed the upper part of the arched label’.

He concluded, ‘This being the case and the roof being in real need of heavy repairs, it becomes a question whether it would not be better to put on an entire new roof, lowering the side walls and restoring the original pitch in harmony with the east window rather than keep up that which though handsome in itself does certainly offend the eye from its incongruity with other features with which it is in immediate contact.’

Without further commentary revealing his own preference, he appended two drawings showing the south and east elevations of a restored roof and a completely new one, together with estimates of their respective costs.

Finally as far as the chancel is concerned, he commented more briefly on the windows and interior of the chancel: the ‘glazing is not in good condition, it all needs releading’ but ‘there are some fragments of stained glass worthy of preservation’. As for the interior, the ‘floor is laid with Yorkshire flags and is in good order. The stucco is not very bad, but would need renewal if the roof were stripped. The pew framing is of poor character and the floor needs some repairs. The communion railing is an inferior one, but in moderately good condition. The South doorway (i.e. the priest’s door) is blocked up and needs restoration with new door etc. complete.’ He then went on to report on the state of the fencing of the churchyard, which it was also the responsibility of the Commissioners to maintain.

The estimate for restoring the chancel in its 15th century form was set at £385, whilst ‘If a new open roof of fir of appropriate outline and character be substituted for the existing flat roof and parapets and placed upon the walls at a lower level’, this would reduce costs by £115. On 18 July 1856 the Commissioners resolved that Christian be asked to get tenders for repairs at £270, ‘making the above mentioned substitution of a new roof’. He wrote to the Commissioners again on 21 January 1857 about the option they had chosen; he had revisited Norwell ‘and reconsidered the question of the roof, an objection having been raised by the Vicar as to the probable effect of a high pitched roof’.

He and Christian eventually agreed that the proposed high roof was indeed the right solution to adopt ‘both for the good effect of the Chancel itself, and also for its harmonious grouping with the various features of the church’. The vicar was also ‘anxious to have the Vestry which formerly existed at the east (sic) end of the Chancel restored, there being none at present’. Christian had, however, made no provision for this in his plans or estimates.

Tenders of £165 from William Lee of Retford for masonry, plastering, glazing and ironmongery, and of £201 5s from Messrs Clipsham (local builders) for the new roof, from which £96 was to be deducted for the old lead, giving total tenders of £270 5s, were accepted by the Commissioners on 22 January 1857 and Christian was ordered to proceed with building. The lead was stripped in March and by May rebuilding work was well underway.

In August a few additional items relating to internal fittings were added at the vicar’s request so ‘that the whole may be completed simultaneously’. These included moving ‘a screen within the Chancel arch, which is not now needed and might be more usefully placed across the South Transept, where it would serve to enclose a Vestry’ (this was agreed at a cost of £11). Secondly, ‘It would be a great improvement to the interior to put new benches instead of the old pews which are very poor. The oak from the old roof might be usefully applied to this purpose. The cost of double benches on each side made of that material would be £34. A new communion rail which would be needed to complete the Interior would cost about £22.’

On 7 September 1857 the Commissioners agreed to the proposals about the screen and railing, but put off making a decision about the benches until their chairman, the Earl of Chichester, had personally visited Norwell to see for himself what was proposed. Six weeks later, the Commissioners sanctioned the £34 for the benches, which were constructed by Henry Clipsham of Norwell.

A comparison of the details relating to the restoration of 1857-8 with what can currently be seen in the chancel and on the exterior of the church shows that little of importance has been changed subsequently, apart from the replacement of the York flags by encaustic tiles during the restoration of the body of the church in 1874-5 and the insertion of a reredos. Structurally, the walls of the late medieval chancel were lowered, the parapets removed, the priest’s door unblocked, the tracery of the east window renewed, and the present ribbed and arched timber roof erected.

In the course of this medieval timber panelling was destroyed, though evidence for some re-use of the roof timbers in the benches, as the written record suggests, can be seen, especially at the base of the double choir benches. It is not clear whether the wooden screen that was moved from inside the chancel arch preserved any early work (was it, for instance, cut down from the original medieval rood screen disestablished at the Reformation?). It was observed by Sir Stephen Glynne in 1874 on the eve of the next campaign of restoration in its new position in the south transept arch, only to be destroyed shortly afterwards.

Similarly, although Christian identified some old stained glass as worthy of preservation, this also has been lost, possibly in later re-glazing of the east window in the late 19th century. It may also have been medieval, though it is more likely to have been fragments of the armorial glass that Thoroton noted in the 17th century. Christian’s ground plan of the chancel in 1857 shows a small interior rectangular structure adjoining the chancel arch at the north-west corner of the chancel.

Inscribed

date Inscribed

date |

This was presumably the vestry which the Rev James Maxfield wished to be replaced; all trace of it was however swept away. Problems over financing this phase of the restoration seem to have been met swiftly without too many difficulties, while the work itself was accomplished with relative efficiency and tact. An inscription in the sedilia adjacent to the altar on the south side of the sanctuary records the date of completion slightly prematurely as 1857 (A.D. C VIII LVII).

b. Restoration of the Rest of the Church, 1872-5

In comparison with the restoration of 1857, that of 1874-5 seems to have generated some controversy and to have been a more tortuous process. The Rev Mr Maxfield had already alerted the Commissioners to the poor state of the main body of the church in 1856, when he compared it unfavourably with that of the chancel. For some years after the chancel was restored, nothing appears in the Commissioners’ files on Norwell. When the Lincolnshire Diocesan Archaeological Association visited the church on 22 June 1871 they noted that it was ‘of noble proportions, but in a very deplorable condition’.

Then on 28 May 1872 there is a letter to the Commissioners from E M Hutton Riddell of Carlton on Trent (and Mayor of Newark in 1874), admitting that he was not a parishioner but simply an interested party. Writing in slightly ironic vein, he said he was sure that the Commissioners knew of the need for restoration, but ‘If not I need only say that it could hardly be in a worse state.’

There had clearly been extensive discussion locally because the builder Henry Clipsham had already estimated that it might cost £1800, of which Riddell thought that only £400 or £500 might be raised by the parish. Almost a month later, the Secretary of the Commissioners wrote to Riddell informing him that Ewan Christian had been directed to survey the building and advise on work to be done.

In the interim, Maxfield had called a meeting with the two wardens and Riddell to decide on what steps to take, and they had agreed to employ an architect to draw up plans that could be sent to the Commissioners. Two days after learning of this, the Secretary wrote to Maxfield about the appointment of Christian to assess what was required.

As in 1857, his report was soon produced; it was sent to the Commissioners on 29 July 1872. Although not quite so detailed as that of 1856 (the body of the church as opposed to the chancel was not the sole responsibility of the Commissioners), it nevertheless makes reference to some aspects of the late medieval features of the church that would be destroyed or altered by the restoration as well as to more recent (often poorly executed) repairs. It reveals how much of the fabric had to be renewed. Once again Christian acknowledged ‘the considerable archaeological interest’ of the church which ‘possesses several features architecturally beautiful’. He identified the main phases of building (his interpretation differing little in broad outline from current views except that he attributes the ‘South Mortuary Chapel’, i.e. the south transept, to the 15th century).

But its state was lamentable: ‘As regards repair the present condition of the Church is one of miserable dilapidation in almost every particular’. The interior was little better: it was ‘in a wretched state, the walls are green with damp, the floor is broken up and scarce safe to walk upon’. He finally gave the potential cost of the restoration as £2604.

After a delay of four months, the Commissioners informed Riddell that they would contribute £1500, leaving £1104 to be raised locally. On 16 December 1872 a public meeting of parishioners was held, with Maxfield in the chair. As he reported to the Commissioners on 30 December, a resolution had been passed at the meeting conveying their thanks for the promised £1500 and pledging to raise the rest by soliciting subscriptions from owners and occupiers of land in Norwell, Norwell Woodhouse, Middlethorpe and Willoughby, from parishioners in general and from others.

The subscription list names 97 pledgers, with sums ranging from £100 (E M Hutton Riddell, whose wife also contributed £25) to 1s (24 contributors). Four collectors had also been sent out with cards, raising £17 8s 6d. Among other notable contributors were the Rev Samuel Reynolds Hole of Caunton (£20), N H Barrow MP (£20), Henry Clipsham and his wife (£20), William Curtis (£60), George Esam (£30) and Joseph Templeman (£52 10s), while the Maxfield family collectively pledged £86, of which £15 was in memory of Maxfield’s three daughters Matilda, Alice and Blanche.

Although the sum raised was not as large as that raised shortly before at Caunton by a similar method, it seems to have been sufficient to convince the Commissioners of the good intentions of the parish to bear its share of the costs, so on 22 May they accepted the vicar’s proposal. But work did not begin until the following year. The death of the Rev Mr Maxfield on 13 August 1873 may explain this delay, because as soon as his successor, the Rev William Hutton, was in post in March 1874, work began. On 11 April, ‘Mr George Sheppard sold by auction a quantity of timber from the interior’ of the church. Another appeal for funds was launched with a leaflet dated 24 July 1874, signed by Mr Hutton and J Templeman as secretary to the Restoration committee.

The subscription list was now headed by the bishops of Lincoln and Manchester and the suffragan bishop of Nottingham (all £10), and the vicar and his wife, in addition to a pledge also of £10, promised a new font. Another source of local funds was a concert held in February 1875 which raised £85 19s 3d towards the restoration, thanks to the help of the Free Foresters Glee Union. Instalments were paid over the course of a year until Mr Hutton could write to confirm on 15 June 1875 ‘that the whole work of restoring the Parish Church of Norwell has been completed in a thoroughly substantial and satisfactory manner’. He commended Clipsham and thanked the Commissioners ‘for the generous aid which has enabled them to restore this noble building’. Locally £1050 had been raised, but additional money was still required.

It was pointed out that ‘absolutely necessary’ additional work was needed to complete the restoration, including the new steps and floor in the chancel, reglazing of the east window, removing earth from around the church, repairing the bell frame, rehanging the bells, installing a new font, rebuilding the churchyard wall, and new entrance gates, totalling expenses of £502 19s 7d, with a final addition of £12 for book desks for the benches in the chancel.

The Commissioners were obviously more accommodating now that the full extent of the costs were clear and in August Mr Hutton was able to thank them for additional help and understanding, while finally on 23 November 1875 Christian authorized the final settlement with Henry Clipsham for £2674 19s 7d. Among items he had supplied were ‘wire doors’ for the chancel and south doorway as well as the book desks for the choir seats. Other records provide some detail on the new fittings which completed the restoration.

The quality of the work can be assessed by its durability: although there were a number of small problems that continued to cause expense in the coming decades, much of what Christian and Clipsham achieved is still in good condition. Specifications for the builder reveal that the main principles on which Christian had worked was to save and restore as much as possible of the earlier church, only replacing material where unavoidable.

For example, old glass quarries from the windows, were reset in windows in the north and south aisles and elsewhere, with a new narrow clear glass surround to indicate the extent of restoration. Glass, old locks, hinges and other ferramenta were to be re-used where possible. In practice it seems that more eventually had to be replaced than was envisaged. But the blending of new and old material was done with such skill that it requires a closer study of the current fabric than has been attempted here to identify all of what was finally preserved from the pre-restoration church.

Appeal

leaflet Appeal

leafletof 1874 |

Detail

of photograph Detail

of photographfrom appeal leaflet |

However, there were some important features which were irrevocably changed at the restoration. The chancel lost its fifteenth-century roof and parapets, which was replaced by the steep-pitched roof in situ; some early glass was removed. In the nave, the clerestory was rebuilt in stone in place of brick. In the south transept, a poor-quality hipped and tiled roof (which can be seen in the photograph which accompanied the appeal leaflet of July 1874) was replaced by a new timber roof in perpendicular style. The porch was completely rebuilt. The tower lost its low spire. All external doors were replaced.

Throughout, York slabs and memorial stones which had provided the flooring of both the chancel and main body of the church, were either removed or covered over with tiles (the original flags can still be seen at a few points in the church), while pews and timber-work like screens, some of which probably dated back a considerable period, were either replaced, burnt or sold, only a small proportion of roof-timber being re-used for the choir benches. No record appears to have been kept of the original location of numerous earlier monuments found in the pre-restoration church, many of which were resited in the south transept during the restoration.

iii. Work on the Church since the Restoration

Upkeep of the church, following the restoration of 1874-5, continued to cause financial difficulties: although a fairly large parish, Norwell was not particularly rich, lacking as it did any long-established gentry families or those who had made their fortunes more recently in commerce or industry.

In 1884, the Rev William Hutton drew attention to the increasing poverty of the village in a time of agricultural depression, when asking the Ecclesiastical Commissioners to assist with current expenses: ‘That as so much of the land in the Parish is untenanted they will as Lords of the Manor be so good as to make a small grant in aid of the Church expenses which cannot now be met as in more prosperous times by the offertory though the people still give to the best of their ability, we are drifting into a poverty-stricken condition of things inconsistent with the dignity of the noble building in which [they] worship’. Marginal notes on his request show that of the 3123 acres in the parish, the Commissioners possessed around 1900, of which 340 were in hand and large reductions of rent had been made for many of the tenants of the rest as a rental indicated. On 24 July 1884, their lordships agreed to pay £5 annually to help cover unavoidable expenses.

Fifteen years later, Hutton’s successor, the Rev William Russell wrote on 11 October 1899 for another £5 for taking up and relaying portions of the chancel and sacrarium ‘where the slabs and tiles are now quite loose and in danger of being broken’. If the work was done immediately, he thought the cost might be as little as £3 but if put off until the following spring this would rise to £10. When it was undertaken, the state of the chancel floor proved to be worse than expected: W H Clipsham had submitted an estimate of £13. By November 1900 he had carried out this work as well as repairing and painting guttering and downpipes.

The next structural feature to require major work was the chancel window. On 25 March 1907, Mr Russell informed the Commissioners that Mrs Brand, whose father formerly owned Palishall, wanted to place a stained glass window in the east end of the chancel, for which Charles Kempe had drawn the design, but that stonework needed restoring. Kempe had recommended Mr Hodgson Fowler from Durham to repair the decayed stonework.

It was discovered, however, that more serious repairs were needed, despite the restoration of 1857-8, not only to the stonework of the east window, but for settlement cracks, repairs to the slating and ridge of the chancel roof and for replastering and colour-washing the walls. Moreover, the work that had been done on the chancel floor in 1899-1900 had proved poor: the tile floor and steps were again in a very bad condition, partly because of concrete laid underneath. While, following extensive discussion over the appropriate design, Walter Tower, who succeeded his uncle, Charles Kempe, installed new glass in the east window in 1908.

In addition Mrs Brand established a small charity in her will (1916), the income from which was to be used partly for the maintenance of this window and for that in the north aisle also earlier erected at her expense, as well as for other purposes.

There is then a gap in the Commissioners’ files on Norwell until 1926 when beetle and damage by damp necessitated the replacement of the wooden floor of the choir stalls and some repair of seats. A few months later the chancel roof required relaying yet again, the priest’s door had to be repaired following a burglary, decayed ashlars in the walls needed re-instatement, ivy needed removing, and problems were still being experienced with settlement under the east and north-east window.

Four years later, on 28 June 1932, the Rev Basil Ainley, once more cited severe local economic difficulties in his request for help from the Commissioners ‘the landlords of almost all the Parishioners’. He reported that the ‘whole village is in very bad financial circumstances and we are faced with a big task at the church because of the ravages of the Death-watch Beetle’. But an appeal was successfully launched and the work completed even though the cost of installing the new bells proved to be higher than expected.

Routine maintenance problems naturally recurred. The perennial problem of rising damp was partly resolved by the installation of new heating at the cost of £400 in January 1952. Most recently, the major structural expenses have been the renewal of the lead on the tower (1993) and nave (1996), this latter costing over £31,000 of which English Heritage contributed 37.3%. Electric lighting was first installed in the church in 1948, although as early as 1929 a lamp had been provided for the church path by the parochial church council.

Part Three: Aspects of church and village life in Norwell

i. In the Middle Ages

Little evidence survives to show how the clergy related to their parishioners and how the latter used the church until relatively modern times. But a few glimpses of the role of the church as a building used not only for services but also as a public meeting place can be discovered for the late Middle Ages.

Late thirteenth- and early fourteenth-century Archbishops of York were frequent visitors to Norwell so that it is not surprising that a certain amount of ecclesiastical business was transacted when this happened. For example, some archbishops summoned clergy to meet them at Norwell where they held their visitation courts.

In a similar way the church was occasionally used by secular authorities for judicial purposes or as a suitable meeting place when matters of public interest were at stake. On 11 November 1360, for example, John Le Parker, a felon of Norwell appeared in the church before the king’s escheator and promised to leave the kingdom forthwith, while his worldly goods were publicly seized by the crown.

A few years later in 1369, another criminal, John Strynger of Mansfield, who had killed a man, took sanctuary in Norwell church, which he too was allowed to quit on condition that within 7 days he would leave the country via Dover. While the church itself had been the scene for violent events in 1335 when a dispute over succession to the prebend of Overhall between John Denton and John de Droxford and their respective supporters led to fighting. This resulted in Denton himself leaving the country in order to take his case to the papal court then at Avignon.

Nearly two hundred years later, in 1526, on the eve of the Reformation, the two vicars of Norwell were called to adjudicate in a local quarrel in which the wives of John Willa, Richard Walbank and William Brownberde had mutually slandered each other. Along with two parishioners, Richard Smyth and John Green, probably the churchwardens, the vicars, Richard Marten and Richard Awbye, brokered a settlement with the husbands agreeing to pay 40s to the Fabric of the church if their wives did not abide by it. But such vignettes of life in the medieval parish are extremely rare.

ii. From the Reformation to Modern Times

| a. | Population Change | |

| b. | Changes in Religious Practice | |

| c. | Vicarages | |

| d. | Churchwardens | |

| e. | The Church, Education and Charities |

a) Population Change

Following the Reformation it is possible to establish in more detail the lives of ordinary parishioners, especially when surviving registers of baptisms, marriages and burials begin in the late seventeenth century. Some extracts survive for a few earlier years, including 1638 which show 16 baptisms (6 boys, 10 girls including one bastard), seven marriages and 16 burials (4 men, 9 women, 3 children) that year. When registers begin in 1681 decennial averages, worked out by Wallace Smith, show that baptisms for the period 1681-90 averaged 13.5 per annum, while for 1691-1700 the figure was 17.5.

Calculating cautiously from this and other information he deduced that the total population of the parish, which included the chapelry of Carlton-on-Trent as well as the hamlet of Norwell Woodhouse, and manors of Willoughby and Middlethorpe, must have hovered around 400 at this period. In the eighteenth century it appears to have remained fairly stable: in the mid century between 10 and 15 baptisms were recorded yearly and baptisms normally exceeded burials, although there were some years of marked mortality. Whereas the average number of deaths was usually around 8 to 10, in 1720-1 at least 27 occurred and in 1727, again, over 20 deaths are recorded so that some kind of epidemic disease can be suspected. Conversely in 1713 there appears to have only been one death. A slow increase in population can thus be posited.

In the first half of the nineteenth century this became much more marked. The first full census of 1801 shows around 420 people in Norwell itself; agregating Norwell and Norwell Woodhouse from the 1821 census onwards, a peak was reached in 1861 when almost 800 people are recorded in these two settlements. But this was followed by a long period of agricultural depression so that in 1881 only around 500 people remained.

By 1891 there had been a modest increase but decline set in again shortly afterwards which continued until very recently. The 1961 census recorded less than 300 inhabitants but since then there has been a modest recovery: in 2001 there were 426 people in Norwell and Norwell Woodhouse.

b) Changes in Religious Practice

Little is known about the immediate impact of the Reformation locally. Most people living in the parish appear to have accepted the changes of allegiance expected of them as monarchs from Henry VIII to Elizabeth I shaped the church in England to their particular design. Richard Alvey, who succeeded as vicar of Overhall mediety in 1534, managed to hold his living unchallenged until his death in 1568, while his contemporary in the Tertia mediety, Thomas Cowhyrde, likewise held his living from 1535-60.

Most lay families followed suit and kept their heads down, though some, like the Sturtevants, do appear to have been reluctant at first to abandon their Catholic faith. This did not prevent them, along with other wealthy families, from competing to obtain leases of the former prebendal estates.

Likewise local reactions to the religious debates of the seventeenth century have left very little trace. Gervase Lee, tenant of Overhall manor, was fined the enormous sum of £500 in Star Chamber in 1608, for a poem which was deemed to be highly scurrilous, lampooning in highly satirical form the comfortable lives led by prebendaries of Southwell, highlighting especially their mercenary and secular attitudes. But he and his family remained staunchly royalist and protestant during the Civil War, their manor house being briefly besieged in February 1645.

Despite the re-establishment of the Church of England following the Restoration of Charles II in 1660, there is a hint of growing disenchantment with it locally. The figures for attendance at communion in Compton’s census of 1676 showed that there were only 147 inhabitants of the parish ‘of age to take communion’ when, as noted above, the total population was probably near to 400.

The census does not name any remaining Catholics in the parish though there were nine dissenters. The early registers also occasionally note the baptism or burial of Quakers. Among those buried, on 9 June 1690, was a certain Edouynon Tuder, described as ‘a minister’: was he perhaps an itinerant Welsh preacher who fell ill and died when in Norwell?

Of the dissenters noted by Compton, some were probably Baptists since in 1672 a member of the Esam family belonging to that sect was licensed to hold worship in his own house though it was withdrawn in 1673. Quakers continued to be active in the parish, though by the time of Archbishop Herring’s visitation in 1743 their congregation was in a parlous state. As for dissenters, these too had apparently now disappeared since the Rev John Townsend reported that of the 105 families in the parish ‘none of them Dissenters of any sort’.

Of his own ministry, he confirmed that he read ‘Public Service’ every Sunday morning ‘except when ye Sacrament is administered at Carlton, which is a Chapel of Ease, and at ye said Chapel in ye afternoon’. Communion was administered six times a year at Norwell and three times a year at Carlton, the number of communicants now having fallen to around 70 at Norwell and 20 at Carlton. Due warning was given, he said, when Communion would be offered, and in recent years he had never refused it to anyone. He also provided a certain amount of pastoral teaching in Lent when Townsend clearly expounded the Catechism ‘and ye parishioners send their children and servants diligently’. He also commented favourably on the teaching offered in the Charity School to 20 poor children ‘instructed in ye principles of ye Christian Religion’.

The remarkable growth of non-conformity in the wake of John Wesley’s missions eventually led to the establishment of a local congregation in the parish: in 1813 the Newark Circuit Plan mentions Norwell as a member, while the establishment in 1821 at Norwell Woodhouse of a chapel in a farm-house, was followed by one in Norwell itself a few years later. The Rev W Sturtevant, ‘a Calvinistic Minister’, ‘gave a piece of ground from his own estate in the centre of the village and erected a Chapel, which he transferred to the Wesleyan Methodists for 60 years’.

This was in 1827, when the chapel was opened on 7 November by the Rev W Fowler of Newark and Mr Sturtevant. The Archbishop of York granted a licence for holding religious services there in 1828. In 1843, on Sturtevant’s death, the Wesleyans bought the chapel outright, and it was re-opened on 6 November, ‘The day being fine, a great influx of visitors from the neighbourhood took place’ and a large tea-party was held. It is this occasion which is recorded on the date-stone still to be seen on the chapel.

The 1851 Religious census shows that the Wesleyan congregation was continuing to flourish, with attendance at most of its services rivalling those of the parish church, while the Methodist Sunday School had more scholars (44) than that of the Parish church (33), despite the fact that the Wesleyans only made up about a fifth of the population. At Norwell Woodhouse, the proportion was much the same: of the 127 adults in the township listed in 1851, 25 attended morning service, 35 afternoon service and 20 evening service on the day of the census, while there were 23 Sunday school scholars. It continued to flourish and 62 scholars were on the register by 1864 and 79 by 1889, with a peak reached in the 1890s when two superintendents and eleven teachers had 90 children in their care.

Non-conformists were also strongly represented in the late nineteenth-century temperance movement, and by the 1880s there was a flourishing ‘Band of Hope’ with no less than 33 members in 1883. The Methodist church itself was enlarged by the addition of a school-room in 1909, built at a cost of £337 by Henry Clipsham and Son, on land bought from the Ecclesiastical Commissioners for £20. A photograph taken on the occasion of its opening shows a large number of attendees.

But as the twentieth century progressed, the regular congregation began to decline steeply after the First World War even though special events were still well-supported. The chapel was extensively renovated in 1949, while for many years the most active local Methodist was John W Bennett. In 1971 he completed sixty years service as organist on alternate Sundays. The last service was held on 19 November 1989 when four people (including two visitors from North Muskham) joined with the Rev Colin Letchford of Southwell. Eventually, in 1991, the Methodist church itself was sold. The building is now a private residence, the nearest flourishing non-conformist church to Norwell being the Wesleyan Methodist churches at South Muskham and Sutton-on-Trent.

Some incidents show that not all villagers were respectful of religious observance. Gervase Lee, son of the Gervase Lee, author of the scurrilous poem about the prebendaries, flouted social conventions by getting into trouble with a puritanical church for lax morals. In 1634-5 he was presented in the Chancery Court at York for adultery with three women. At a private session he eventually agreed that he had had sexual relations with his (second) wife, Eleanor Rokeby alias Thorneton, after their marriage had been contracted but before it was solemnized. The remainder of the case was then dropped, his penance being commuted for an unspecified monetary payment.

In 1636, as impropriator of the tithe of Norwell, Lee was again cited before the visitor for failure to repair windows and walls in the chancel for which he was responsible. This did not prevent him promoting his own family interests: an elaborate wall-monument in Renaissance style, now in the south transept, commemorates his first wife, Elizabeth Ayloffe (d.1629), mother of sixteen children, eight of each sex.

In April 1796 William Templeman and William Cook, butchers, were charged with ‘maliciously and contemptuously disquieting and disturbing a congregation assembled at Norwell for public worship’. But the case did not stick and they were discharged: perhaps it was simply a question of an excessive intake of alcohol.

This was certainly the case some seventy years later when a party of labourers who had been drinking at Brownlow’s Beerhouse in the village left with additional supplies which they proceeded to finish in a nearby field, along with the landlord’s son. But in a short time they had fallen out ‘using disgusting and blasphemous language not far from the Church, where Service was in progress’. When it was finished, and seeing people still ‘hurrying excitedly towards the field’, the Rev Mr Maxfield rose magnificently to the occasion and ‘going there, without much trouble put an end to the disorder’.

c) Vicarages

The present vicarage in Main Street is the latest in a long line of buildings that have served that function. The earliest is mentioned in 1310 when one of the vicars, Henry of Edingley, was fined by Archbishop Greenfield of York for failing to keep the vicars’ house in repair as he had been instructed at a previous visitation. The location of this house in which the vicars of the two medieties were probably living communally is unknown, but it is likely to have been close to the church.

An entry dating from 1433 in the White Book of Southwell seems to confirm this since it describes a group of adjacent houses to the west of the church in which both John Hans, ‘clerk of the parish’ and Robert de Northwell, a former chantry chaplain, had once lived. Both were probably in what is now Old Hall Lane, not far from the first of the surviving former vicarages of Norwell, now The Grange.

With the Reformation allowing clergy to marry, it is likely that at least two houses were needed in the early modern period as vicarages for the holders of the medieties. That held in the late seventeenth century by William Bayes, vicar of the Tertia Pars mediety, is described in the earliest surviving terrier (1687) as ‘containing four Bayes of building, and a Barn of two Bayes, and a Stable one Bay, and the Yard belonging to it containing half an acre’. This was clearly a substantial wooden-framed building (a bay was usually about 16' x 16' in size).

Later terriers continue to describe it in very similar terms until the mid eighteenth century, though by 1743, following the amalgamation of the two medieties, it was divided into two separate residences. By 1764 ‘there was only the skeleton of a poor clay house when the present Vicar came hither, and for which he neither expected nor received any dilapidations, as the separate Medieties appeared to be insufficient maintenance, and therefore suffered to be taken down and applied to the maintenance of other premises’. Where the Tertia Pars vicarage was sited has not however been clearly established.

Another terrier in 1714 refers to two vicarage houses, two barns, one stable, two cow houses, two gardens and other conveniences and fences in good repair; that of Overhall in 1726 is described as a ‘Dwelling House, three bayes, one barne three bayes, stable and beast house two bayes, one rood of ground adjoining upon the homestead’. Again, all these buildings were still apparently of timber-frame construction, as they were in 1743, 1748 and 1759 when the next three terriers describe them in similar form. But by 1764 major changes had clearly occurred.

There was only one ‘Vicarage House’ and this was now substantially built of brick. Without any further major changes, this building served as vicarage until the late nineteenth century. Then fears were expressed over worsening conditions, especially problems with damp (three daughters of the Rev James Maxfield had died of tuberculosis), so that it was decided to build a new vicarage. Tenders were invited in July 1888; the architects were Naylor & Sale of Derby.

The new dwelling (now The Old Vicarage) was erected on higher ground, commanding fine views over the village and beyond, set back behind the old vicarage at the end of a winding drive from the Cromwell road. In 1948 running water and electricity were installed. But eventually, with changing social conditions, the late Victorian vicarage was deemed to be too large and expensive in upkeep for modern purposes. In turn, it was sold in the early 1970s, becoming like The Grange, a private residence still happily in use, while a ‘New Parsonage House’ was constructed appropriately on glebe land alongside The Grange, not far from the west end of the church, where there has been an almost continuous sequence of dwellings for clergy serving the church and parish since the Middle Ages.

d. Churchwardens

What is known about those who served as churchwardens over the centuries? A document in the White Book of Southwell mentions William Baker and John Irland as the ‘senior keepers of the fabric of Norwell church’ around the year 1410: they are the earliest known churchwardens. In 1526 Richard Smyth and John Green, probably churchwardens, assisted the two vicars in settling a dispute between some women of the village. No other wardens are recorded by name before the mid seventeenth century.

However, from then until the present a continuous list can be compiled. It represents, especially for the seventeenth to nineteenth centuries, a roll-call of most prominent families and office-holders of the parish since many of them also served as Constables or Overseers of the Poor as well as wardens and trustees of the charities. Among the most frequently encountered family names as wardens before 1900 are the Sturtevants, Esams, Elvidges, Parrs, Roses, Taylors, Curtises, Templemans, and Woods, with the Esams (Richard in 1658, George in 1881) perhaps having the longest representation over many generations.

Between 1651 and c1720 it was normal practice to change both wardens each year, even if some men served on more than one occasion. It was unusual however for anyone to serve more than three or four times during their lives. From around 1720 it became more usual practice for men to serve two or more years in succession, sometimes a year as vicar’s warden and another as people’s warden.

In the late eighteenth century the practice of short and alternating terms of office among a reasonable spread of local families began to change. From 1798-1816 Leonard Esam, who had already served as people’s warden in 1787-8 and 1790-1 was vicar’s warden, though to counteract this the people’s warden was usually changed annually. This practice continued under Samuel Curtis, vicar’s warden from 1816-34 though the corresponding people’s warden often held the job for two or even three years.

The tradition of the vicar’s warden holding his post for many years in succession has continued into very modern times when the term itself has been dropped though each warden continued to have a different portfolio of responsibilities. Curtis was succeeded by yet another Leonard Esam (1836-64), who was in turn succeeded by George Esam (1864-81), Joseph Hardy (1886-1900), Arthur William Dobbs (1900-04 and 1910-25), Robert Marston (1926-67) and Evelyn Marston (1967-82).

Such continuity was unusual for the people’s warden until Joseph Templeman, senior, who held the post from 1869-78. Evelyn Marston became people’s warden in 1938 so that for thirty years the two Marston brothers served jointly as wardens, while on Robert’s death, Evelyn then assumed the role of vicar’s warden until 1982, a dominant family presence in local parochial affairs that is unlikely to be equalled as is Evelyn Marston’s continuous service as a warden for 44 years.

e. The Church, Education and Village Charities

Norwell is unusual and fortunate in still having three adjacent standing buildings in School Lane that have served as schools since the early eighteenth century: the ‘Old’ charity school founded by Thomas Sturtevant in 1727, the Victorian or National Endowed School built in 1871, and the current Church of England School opened in 1966. They reflect in a very concrete fashion many of the major changes which have occurred in education over modern times. Their history is closely bound up with local charities and the parish church

Although it may be presumed that some vicars of Norwell provided instruction or tuition to local children (many from the seventeenth century were graduates), little is known about opportunities for education in the village before the establishment in 1727 of a Charity School. This was to be administered by named Trustees, usually including one or both churchwardens or former churchwardens, as well as other prominent local figures. The main benefactor was Thomas Sturtevant of Palishall who endowed the school with lands and rents worth around £20 p.a.

In 1733 another Norwell inhabitant, Mary Wilkinson gave a further £40 ‘for the most diligent in coming to school’, while the clerk to the Trustees, Robert Marsden added a further £50. Other benefactions from John and Mary Green also accrued so that the Trustees were able to spend that same year £164 2s on purchasing land at Well-fen Closes at Claypole, Lincs. From the income, 5/12ths of the rent was ‘to be paid to the schoolmaster and his successors for ever, for teaching so many poor children to read, write and cast accounts as the Trustees should think fit, and 4/12ths to such poor children of the School for ever as were most diligent in coming to the School and of good behaviour ...’. By that point 14 boys and 14 girls were attending regularly.

A later benefaction was specifically intended to provide poor pupils with uniforms: in 1768 Mary Sturtevant and her husband, Leonard Esam, gave £100 ‘to be placed at interest’ from which payment was made for blue cloth for coats and caps for the boys, and blue ‘stuff’ for girls, distributed annually on Easter Sunday. In addition Margaret Sturtevant provided for £3 to be paid a year to a baker for supplying weekly 15 penny loaves to be distributed after Sunday service by the Churchwardens not just to children but to any deserving poor.

The same sum was still being assigned for this purpose until well into the twentieth century: in 1922 a local miller, F Jackson, was paid £3 for bread which went to five recipients and he received £3 again in 1927, though the number of recipients is not known. It is not clear when the supply of school uniforms ceased but they were still being distributed as late as 1931.

The last important eighteenth-century legacy was from Samuel Wood who in 1782 left £80 for the school, directing that it should be used for the education of four poor boys between the ages of 8 and 12, two to be natives of Norwell and two from Norwell Woodhouse.

Whilst the Charity School was obviously flourishing in the early nineteenth century, one or more private schools were also established in Norwell. In 1807 an Oxford graduate, the Rev Mr Foottit (a family with that name had been present in the parish since the seventeenth century) was accepting eight to twelve pupils who were offered a syllabus which included ‘Classical, Mathematical & Commercial Learning’.

In 1825 an advertisement for ‘Mr Wilson’s Boarding School’ stated a fee of 20 guineas a year without extras (printed books and washing), with Classics and French even taught by a native. Pupils were expected to furnish ‘a pair of sheets and towels’. This school (almost certainly located in modern Schoolhouse Farm) was still going strong in 1833 with the same fee and a curriculum that included ‘English grammar, Geography (illustrated by Maps and Globes), History and Land surveying’ among other disciplines.

The first mention of a Church Sunday School occurs in 1834 when it was attended by 90 children, perhaps more than attended the Charity School during the week. On the day of the Religious census of 1851 there were 33 scholars present both in the morning and afternoon. An Enumeration census of the same year showed that the day school had by then 72 scholars. In 1855 Mr and Mrs Woolhouse celebrated their eighteenth anniversary as Sunday-school teachers; they finally retired in 1870 after 25 years service as the village schoolmaster and mistress.

Since 1845 there had also been a Wesleyan Sunday School in the village. Both Sunday Schools were to flourish well into the twentieth century.

State intervention in education only came slowly during the nineteenth century: the Charity School was still not subject to government inspection as late as 1867. It was the Trustees who held quarterly meetings at the School House to examine ‘the conduct of the master’ whom they could dismiss on six months’ notice ‘for intemperance or other misdemeanours’. But the Foster Education Act of 1870, by which free elementary education was to be offered to all, stimulated locally as it did nationally a debate on future provision.

By then, the original building erected through Sturtevant’s charity was nearly 150 years old and no longer large enough for all the children eligible to attend school. It was also somewhat decayed so the decision was taken to rebuild alongside the old school, ‘a plain poor building’ according to Henry Clipsham, who built the new school just as he was to carry out restoration of the church a few years later.

Land was donated by the Denison family of Ossington and the foundation stone was laid on Easter Monday, 10 April 1871, by Speaker Denison himself, who with the Ecclesiastical Commissioners, was the major donor to the new school, giving £200, double what the Education Department provided. As the Trustees announced, with a liberality that Thomas Sturtevant would certainly have approved, ‘The Endowed School of Norwell is a Church of England School, but the Trustees have inserted a clause in the new Trust Deed that “no child shall be required to learn any Catechism or other religious formulary or attend any Sunday School to which the parents object on religious grounds”’.

Good reports were received from HM Inspectors of the education provided in subsequent years by Mr Nolan: in 1876 there were 69 pupils in his care, though the new school could allegedly house 120 according to Kelly’s Directory. Doles of clothing, bread and money (for foundation scholars) continued to be distributed to poor pupils under the terms of the many charities which had been established since 1727, while the Vicar was still expected to preach a sermon to the school on Ascension Day.

The schoolmaster and his wife, traditionally the schoolmistress, lived in a little-modernised School House attached to the Charity School. Yet it continued to be occupied by successive teachers. Lewis Merry Hill, for example, died there in 1933 after 24 years service to the school. In the previous year Nottinghamshire Education Committee had decided to reduce the staff from Head Teacher, an uncertified Teacher and a Supplementary Teacher, to Head and Supplementary Teachers only, posts which Hill and his wife had long held.

At that point it should also be remembered that the school leaving age for those who did not succeed in gaining a scholarship for secondary education was fourteen, so that many village children received their entire education in the school, conditions only changed by implementation of the Butler Education Act of 1944. For much of the earlier part of the Twentieth century, absence from school by pupils in order to assist with agricultural tasks at busy times of the year was a matter of concern to the headmaster, who also noted in the Log Book that some absented themselves to attend sales and follow the hounds.

Eventually the Dickensian conditions of the Victorian school together with changing public attitudes to what was appropriate for primary school children led to plans for a new, third, school to be built on church land facing the two earlier schools in School Lane. This was opened as ‘Norwell Church of England School’ by Lt-Col. Max Denison, great-nephew of Speaker Denison, in 1966, who drew attention in his speech to the fact that the earlier school had cost £500 while the new one cost £25,000. There was accommodation for 80 pupils in four classrooms.

In 2008, there is a Headmistress and three other teachers, and around 60 pupils on the roll. Whilst most of the expense is borne by the County, the earlier charities of Norwell continue to make modest contributions in money or kind both to the school and to individual pupils. Links with the parish church also continue to remain strong, with regular visits to the school by successive incumbents and many reciprocal visits by the entire school to the church for study, worship and social occasions. Sturtevant’s original endowment for a regular sermon (now to be preached on Holy Thursday) still stands but pays only 50p. As for the Victorian school building, this is today chiefly used by the local Scouts and Cubs.

It is interesting to record the most recent administrative history of the various charities founded with educational purposes in mind or closely linked to the parish church since the eighteenth century. In 1905-6 most of these were amalgamated to form the Norwell United Charities with an augmented board of Trustees. Most recently, in 1983, the Charity Commission simplified this dual system so that all the charities are presently administered through the Norwell Educational Foundation.

Other twentieth-century benefactions such as Brand’s Charity (established in 1916 by the will of Mrs Brand) or Colonel James Craig’s Charity (established in 1911, and which in 1931 distributed £9 5s in money to 22 parishioners), both administered by the vicar and churchwardens, have also now been incorporated into what were the United Charities and so come under the umbrella of the present Foundation.

Social concern in the nineteenth century encouraged the establishment of various means for improving the educational well-being of congregations. Sunday school for children, for example, was already flourishing locally by 1834. On 29 January 1889 a decision was taken to found a Church Institute for men. This was to have a Reading Room, to be supplied with papers, and a Social Room for games and conversation. The Vicar, Mr Hutton, was elected President and Mr A Mycroft as secretary and treasurer.

The Institute was to open five nights a week, and a library was soon added. New regulations were drafted in 1911 and 1913. The Institute admirably filled its original purpose by providing recreational and self-improving opportunities for men of the village, the presence of women normally only being noted when refreshments were required for social events.

The Second World War brought a temporary closure of the Institute in October 1939. It opened again after the war in 1949. A final entry records that the Institute was to open for the 1951-2 session on 1 October 1951. However, times had changed and the Institute withered away shortly afterwards if the lack of records and collective memory can be trusted.

iii: The Church in the Twentieth and Twenty-first Centuries

Despite the two World Wars, Norwell changed only slowly. The arrival of modern services such as piped water, electricity and sewage disposal, for instance, took many decades to achieve and was not complete until the 1970s. Agriculture still predominated for much of this period, and the village continued to suffer from long-term economic depression in this sector, especially evident in the 1930s. The sale of farms by the Ecclesiastical Commissioners to sitting tenants in the 1950s did not immediately reverse this, and there was a declining population until the 1960s.

Then amalgamation of farms to provide larger units, mechanisation, subsidies and opportunities for villagers no longer engaged in farming to find employment outside the parish, thanks to better transport, led to new growth. From the 1980s, especially as electronic means of communication encouraged the trend of working from home, an influx of new residents began. The development of former crewyards for new residential housing, especially in the last few years, has boosted the village population to levels not seen since the late nineteenth century.

A snapshot of parish life on the eve of the First World War is provided by Bishop Hoskyn’s visitation of Norwell deanery in 1911. ‘The occupation of the whole population in this deanery is connected with agriculture. Upon the farms work many labourers, who are hired from year to year ... It was sad to hear of the way in which farm lads, who may have passed the fifth standard, forget how to sign their own name, and lose the power even to read ...’.

He also commented on how work on a Sunday morning hindered worship, though ‘I met with quite sufficient evidence that where a farmer and his wife have the will to observe Sunday morning, they find the way. But another curious fact came to light ... In village after village, even though the landlords were Churchmen, the farms are given to and occupied by Nonconformists. How this comes to pass I do not stay to enquire, but it adds very greatly to the task of united work in a small village ...’.

Following the Great War a key event was the dedication of the War Memorials in 1921. Provision for burials locally was enhanced by the decision to extend the churchyard in 1924. The peal of three bells was rehung in a new frame in 1932 after death-watch beetle had been found. In 1934 a fourth was added in memory of William Harpham, warden from 1911-25 through the generosity of his widow, while the peal was finally increased to six to commemorate Queen Elizabeth II’s Silver Jubilee in 1977.

Showing the chancel in c.1930, Showing the chancel in c.1930,with the previous organ |

An organ was installed around 1930 on the south side of the chancel to replace an earlier harmonium, but inconveniently it partially obscured the congregation’s view of the sanctuary. So in turn, it was replaced in 1977 by another organ, only the console of which remains in the chancel while the pipes have been placed high up on the west wall of the nave. One other modern addition was the church clock which was installed in 1953 on the western face of the tower to celebrate the Queen’s coronation.

Parochial church minutes when Bishop Henry Mosley made a visitation in May 1936 are illuminating on more ordinary aspects of village life as the church tried to come to grips with social, cultural, economic and technological change as the twentieth century progressed. There were some good signs: the bishop, for example, ‘expressed his delight that our Church was one of the few where the numbers [of Communicants] were increasing’ (though a register of services shows the number attending Holy Communion seldom reached double figures except at Easter!).

When he asked about average congregation size, he was told that around 20 people attended morning service while the figure for evening service was around 80, ‘which his lordship said was satisfactory in view of the population, and being an Agricultural Parish, which he appreciated was difficult on account of the Stock requiring feeding etc.’

But there were also less encouraging trends too: the Church of England Missionary Society branch had ceased to function since his last visitation in 1931 since ‘unfortunately we could not get the young men interested’. When he inquired ‘what interest there was for the girls’, he was informed ‘that it was practically impossible to start a Branch of any description’.

The bishop clearly analysed how the church more generally was being affected by what he called ‘this rapid change’. There was, he said, no question that as a result of ‘motor cars, the easy means of getting about, the Church attendances throughout the Country generally had gone down enormously’. He then asked a most interesting question. Did we consider the Wireless from a Church point of view an advantage or a disadvantage? Personally he said that no doubt there were many people who did not attend a place of worship at all, but where they had a Wireless Set and listened to the various Services then it must be argued that it must be of considerable ‘benefit’. BBC TV’s ‘Songs of Praise’ perhaps best fulfils the same role in today’s society for a population that has largely given up the habit of regular church attendance.

Reading other parochial church council minutes of the years between the two World Wars and comparing them with those of more recent decades reveals that despite the many changes briefly noted above, much of the traditional patterns of church services and the annual round of social events connected with the parish church essentially remained in place until very recently. The register of services tells much the same story; the number of regular communicants after 1945 remained very similar to pre-1939 levels: usually a mere handful of 3-7 persons.

There was, of course, adaptation and evolution: Garden fetes and then a briefly revived Norwell Feast later became Strawberry Teas. A Son et lumière event recounting episodes from the village’s history in both 1967 and 1969 staged in the churchyard drew most of the community together, as did a communal play with much the same purpose performed in and around the church in 2005 as part of The Festival of The Beck. The Sunday School has become Kid-Zone; in the week a Play-group meets but in the Village Hall rather than the church; the Mothers’ Union now functions jointly within a number of local parishes, but the Norwell Women’s Institute meets regularly. Overall, an impression emerges that by the 1970s an older, more leisurely, world had irrevocably gone.

This was, of course, the moment when the vicar could no longer devote his energies exclusively to the parish but accepted further responsibility for neighbouring ones too: part of a more general response by the Church adapting to changing conditions of falling income as well as falling attendance. In contrast to the 1930s when a regular congregation, at least for evening services, of around 80 could be expected, figures for the last two or three decades have been much more modest.

Naturally the number of services has also fallen from at least regular weekly Sunday morning and evening services still held in the early 1970s to a monthly rota for the joint-benefice of Norwell, Caunton, Cromwell and Ossington. In 2008 this will permit only three regular services a month at Norwell: a communion service, one evening prayer and a family service or a second communion service, if a priest is available, since the current incumbent has eight parishes in her care. Training for laity to lead acts of worship is being encouraged. But the local congregation will inevitably in the near future have to take over even more tasks formerly left to the parish priest if it wishes to preserve regular worship in the ancient and beautiful church of St Laurence, Norwell.