For this church:    |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

Drawing

of Drawing

ofNorman capitals |

| Drawings of Saxon capitals | ||

The foundation stones of the piers of the tower consist of various fragments of a much earlier building, probably Saxon, or very early Norman. They consist of capitals, shafts, bases, arch mouldings, and plain ashlar of strong grit-stone, and are in excellent preservation, packed together in a tolerably sound manner with very little mortar. The ornaments are the interlaced Norman, terminated with the Romanesque honeysuckle or lotus of large size, and of excellent workmanship. The faces of many of them have been painted in distemper in various colours, such as red, blue, etc. and the probable date is from the year 1100 to 1150. The most perfect capitals were found at the base of the north-west pier and formed the quoins at the angles of the square tooling – they had evidently been inserted directly after the destruction of the ancient edifice, as the crimson distemper colour with which they had been enriched was in most parts quite fresh. The foundation of the south western pier contained a mutilated capital, which exhibited some beautiful foliage and many fragments of zigzag arch mouldings.

During the excavations mentioned by Glover:

Floor

tiles from Floor

tiles fromvarious eras |

... many very beautiful specimens of encaustic or inlaid paving tiles were likewise found: indeed a complete series of different ages and design might have been formed had they been collected together. The most common variety is about 5½in square, highly glazed, and contains a shield bearing three lions, fleur-de-lys, etc. These tiles, as they are also the most common, are also of the latest date, and probably formed the original pavement of the present church. Others, which are about 4¾in square, appear to be the next in point of age. They have various patterns of elegant foliage and diaper work of lozenges, circles, and quatrefoils, which, when properly fitted, produce beautiful combinations. These we may with safety refer to the decorated period of the middle of the 14th century; they are in general of better workmanship, and have a more even surface than the others. Another variety is 4½in square, and have the device of a bell, a key, and a sword upon the same tile. The most ancient, which may be Norman, or at least not later than the Early English period, are 3in square, and contain rude designs of a greyhound and other animals.

A number of these tiles, which are broken, can be seen set into the floor to the right of the lectern.

Cottingham’s 1842 report on the tower stated that he was alarmed to find that seventeen ancient graves had been sunk around the piers, up to four feet below the foundations, and the angles of the stone work had been cut off to create space for them. The whole of the spreading footing had been removed, except a few stones at the south-east corner of the south-west pier. Three graves contained lead coffins. The graves were carefully removed, leaving the top of the rock in the worst state of insecurity he had ever witnessed; the edges of the graves were crumbling in from the pressure of the tower above, which threatened to crush the remaining fragile stone. There was a large brick vault (the 1632 Plumptre vault) on the east side of the north transept abutting on the pier of the tower, which had tended to weaken it: a portion of that was removed to make room for the concrete he used to stabilise the structure.

William Stretton, early 19th century Churchwarden and Architect at St Mary’s, had recorded in the floor of the church six grave slabs inscribed with foliated crosses. These are now to be found cut to fit the ledge at the base of the interior walls. He also recorded three inscribed grave slabs, one dedicated to Richard Samon, Mayor, dated mii ivc xxvii (1427), now to be seen in the floor of the church at the north side of the west end; one to John Plumptre (dated mdlii - 1552) and one undated to Richard de Bradmere, neither of which we have identified.

Former Norman window Former Norman windowin nearby Birkin building, possibly from St Mary’s |

In a passageway on the south side of Broadway incorporated into the Birkin building are the remains of a Norman double light window. It has been suggested that this may have been from the previous St Mary’s church.

The base of the fourth pillar from the West end of the North aisle consists of several stones from the piers of a previous church. Recent examination has shown that the deeply incised stone was probably late Norman. It can be examined if the floor boards are lifted.

Thoroton’s drawing of the Thoroton’s drawing of thechurch, dating from 1677 |

Robert Thoroton’s 1677 illustration of St Mary’s from the North West shows its appearance as very like the present church. However, the west end has been replaced twice since then. Nothing remains visible of the 1726 heavy classical-style front with its three round-arched windows, pediments and urns which was demolished in 1848 making way for the present perpendicular style west end. Additions to the north side of the church include the Chapter House, the Choir Vestry and kitchen block and a store room. On the south side of the chancel is the Lady Chapel constructed in 1912-13.

The interior walls are not plastered and although Thoroton recorded a huge wall painting on the north wall of the chancel, this no longer exists and changes were made to the wall for the installation of the 1871 Bishop & Starr organ. On the south wall above the entrance to the newel staircase, and above the memorial to Thomas Smith, is to be found a filled-in doorway which marks the entrance to the ringing loft formed by a platform at the crossing beneath the tower which was illustrated by TC Hine. This doorway had previously been the entrance to the medieval rood loft. A new ringing chamber was created in the tower in 1812 when the old loft was removed and a new groined ceiling made of oak and stucco was introduced by William Stretton.

Up on the south side of the nave roof, at the clerestory a large decorative gargoyle, the only one on the “body” of the church, marks a break of three inches on the line of the cornice.

On the north east buttress of the east wall is a scratch dial. On the north side of the same stone is engraved “XM 1553”.

On the east wall of the south transept are the damaged remains of an Angel which marks the previous existence of a chantry chapel.

During the restorations of 1846, an alabaster tablet (22½" high by 13" wide) was found buried face down beneath the medieval choir stalls. Also discovered were some sixty to seventy coins in the soil, within six inches of the surface. They consisted principally of brass and copper counters, commonly called “Abbey money.” Amongst the coins thus found were a silver penny of King Henry VII or Henry VIII, a sixpence of Elizabeth I, an Anglo-Gallic coin struck off in France when the English were in possession of that country (Henry II’s coin of silver, but the head and inscription nearly obliterated), a lead coin of 1618 called a “Trial Piece,” and a Scottish coin with the date effaced. With the coins were a dice and a lead bullet.

of significant events

The 15th-century font is now to be found in the south west corner of the church. A ground plan of the church dated 1839 shows it to have been just behind the chancel arch at that time.

Significant dating of the building:

Nave and transepts

14th-15th-century

Perpendicular

Nave and transepts

14th-15th-century

Perpendicular

South porch and

south transept Samon tomb 14th-15th-century

built concurrently with nave – marked with mason’s marks indicating

the same mason as nave

South porch and

south transept Samon tomb 14th-15th-century

built concurrently with nave – marked with mason’s marks indicating

the same mason as nave

Chancel recorded

in the Register of 1625 as having been “in great decaye”, and had

been repaired

Chancel recorded

in the Register of 1625 as having been “in great decaye”, and had

been repaired

Tower late 15th-century,

piers rebuilt in 1840s

Tower late 15th-century,

piers rebuilt in 1840s

Chapter House built

in 1890

Chapter House built

in 1890

South or Lady Chapel

built 1912 using masonry from south wall of chancel

South or Lady Chapel

built 1912 using masonry from south wall of chancel

Choir vestry, kitchen & toilet

built in 1940 on north side of nave

Choir vestry, kitchen & toilet

built in 1940 on north side of nave

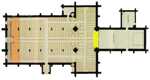

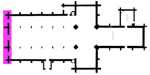

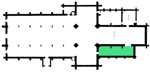

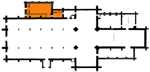

Plans of the building showing the stages of development

Significant archaeological features in the standing fabric:

12th-14th century – under-floor

remnants, floor tiles, stone coffins & tombstones

12th-14th century – under-floor

remnants, floor tiles, stone coffins & tombstones

14th & 15th

century – tombstones, chantry chapel angel, paving, chantry door

with medieval ironwork

14th & 15th

century – tombstones, chantry chapel angel, paving, chantry door

with medieval ironwork

16th-century -

scratch dial and stone engraved “XM 1553”.

16th-century -

scratch dial and stone engraved “XM 1553”.

17th & 18th

century – Plumptre vault, tower graffiti ‘CMS 1660’

17th & 18th

century – Plumptre vault, tower graffiti ‘CMS 1660’

19th century – renovations,

new crossing piers, clerestory, south transept window, new chancel door & infill

of old door

19th century – renovations,

new crossing piers, clerestory, south transept window, new chancel door & infill

of old door

20th century – Lady

Chapel, Choir Vestry, store, kitchen, toilets, tower & bells, new doorways,

south aisle roof

20th century – Lady

Chapel, Choir Vestry, store, kitchen, toilets, tower & bells, new doorways,

south aisle roof

Since 1994 the church has been studied by The University of Nottingham’s Institute of Engineering, Surveying and Space Geodesy and a survey undertaken. The findings so far: the nave floor drops by 10cm in distance from the transepts to the west wall a gradient of approximately 1:400; a typical pillar has a list of 8cm in an approximate north-west direction; the north wall is leaning outwards typically by approximately 10cm.

At the end of the 1990s a paving stone on the north side of the church became loose and, when lifted, revealed the existence of space beneath, possibly the previous coal cellar. It was not explored and the stone was immediately cemented into place in the interests of health and safety.

It was around this time that workmen removing paving stones at the east end of Kayes Walk revealed one of the graves that had previously been within the churchyard but were incorporated into this pathway when the walls were constructed at the beginning of the 19th century, reducing the area of the churchyard.

Medieval Cross Slabs

Cross slabs 1-6 Cross slabs 1-6 |

Cross slabs 7-12 Cross slabs 7-12 |

Cross slabs 13-14 Cross slabs 13-14 |

(1) 0.3 m beneath the level of the present nave floor, and now visible beneath a glass panel, on the north-east side of the third pier from the west of the north arcade. Upper part of slab with incised straight-arm cross and simple fleur-de-lys terminals.

(2) Under a similar panel on the north-east side of the north-western crossing pier. Lower part of slab with an incised cross shaft and base with a trefoiled ogee arch. The remainder of the slabs have been re-used in the wall benches on south (3-6) and north (7-12) of the nave, and are often partly hidden by radiators and heating pipes. Parts of the benches are concealed by modern fittings, or stacked furniture, so they have not been fully examined. All bear incised designs unless otherwise stated.

(3) In south aisle 3m east of south door. Cross shaft with trefoiled ogee arch base and what may be the lower terminal of the crosshead.

(4) East of (3); section of slab with shaft only

(5) East of (4); upper part of slab, round-leaf bracelets on straight-armed cross with horizontal band/label behind shaft.

(6) In eastern bay of aisle. Long slab with cross shaft with cross-band at one end and what looks like a square-ended arm near the other – hard to interpret.

(7) In north aisle, second bay, under 1753 wall monument to Samuel Wright. Tapering slab, cross shaft and remains of head with fleur-de-lys terminals.

(8) West of the doorway to the vestry. Cross shaft and traces of stepped base.

(9) East of vestry door. Cross shaft with trefoiled ogee base.

(10) In fourth bay; one terminal of cross head only, cross bar below fleur-de-lys with upturned leaves.

(11) Opposite easternmost pier of north arcade, the merest traces of a four-circle cross head carved in relief.

(12) East of door in easternmost bay, straight-arm cross with fleur-de-lys terminals.

(13) This is the only one of the slabs figured in the Stretton MS (plate II, no. 3, between p.132 and 133) that can now be traced; in the floor at the west end of the north aisle and now in two pieces, trimmed so that all but the merest traces of the former marginal inscription is lost. Straight-armed cross with fleur-de-lys terminals with a shield, bearing arms, overlying the upper part of the shaft. Pedestal base. The Stretton drawing gives the inscription (perhaps shown in a simplified version) as

| Hic iacet Ricardus Stanton junioris obit mensis…. Anno dom mil ivc xxvii. |

(14) Slab forming wall bench in second bay from west of south aisle, partly cemented over. Incised cross shaft and top of stepped base.

Descriptions and illustrations of cross slabs courtesy of Peter Ryder.

Technical Summary

Core fabric C14-15th Major

medieval urban church

Core fabric C14-15th Major

medieval urban church

Restorations from

1807 to 1890

Restorations from

1807 to 1890

marks inscribed in various places

around the church.

Significant Interior Features

Majority of core

fabric medieval

Majority of core

fabric medieval

Various furnishing

and fittings added mid-late C19th

Various furnishing

and fittings added mid-late C19th

Medieval and later

monuments in N.aisle and N.transept

Medieval and later

monuments in N.aisle and N.transept

Font C15th

Font C15th

Timbers and roofs

| Nave | Chancel | Tower | |

| Main | Mainly C19th | Truss with arch braces 1872 | Fan vault in wood & plaster c.1820 |

| S.Aisle | C19th | ||

| N.Aisle | C19th | ||

| Other principal | Porch stone, early C15th | ||

| Other timbers |

Bellframe

Steel frame of 1935 by Gillett and Johnston, extended in 1980 by Eayre and Smith. A rehang is implied in the 1590-1 accounts, and in 1699 it is recorded that the timber frame was in ‘great decay’. The frame was lowered in 1699 by 22 feet (6.7m); the work being undertaken by John Crow. In 1759-60 the frame was extended to take two new bells and a year later, in 1761, the bells were increased to ten in number.

Not scheduled for preservation Grade 5.

Walls

| Nave | Chancel | Tower | |

| Plaster covering & date | |||

| Potential for wall paintings |

Excavations and potential for survival of below-ground archaeology

Prior to 2012 there had been no significant archaeological excavations. In 2012 Trent and Peak Archaeology conducted an archaeological watching brief during the renewal of floor levels. Evaluations and a desk-based assessment had been ongoing since 1996. The groundwork was limited to a depth of c0.45m and the typical stratigraphy encountered comprised a construction layer of crushed mortar, plaster, and stone overlying a layer of dry, silty-sand containing disarticulated human remains and fragmentary coffin furniture. There was evidence of significant structural remains including an earlier phase associated with the foundations of both north and south transepts. It would appear that the current layout of the church may follow an earlier, cruciform plan, typical of 11th and 12th century churches. Artefacts included fragments of window glass, and glazed floor tiles – some with identifiable patterns including the arms of the d’Eyncourt family. Post medieval burial evidence, in the form of brick-lined shafts containing coffins, was present on the north side of the nave. The Plumptre burial vault was also partially exposed and recorded.

The C19th restorations will have had a significant impact on the archaeology both below ground and within the standing fabric. The construction of a new vestry in 1890 will have had a major impact on stratigraphy to the north of the building. The cutting of paths and general landscaping and drainage of the churchyard will also have had a significant impact on the buried archaeology. However, despite these localized intrusions, the prospect of surviving medieval archaeology is considered generally to be high.

The overall potential for the survival of below-ground archaeology in the churchyard is considered moderate-high and below the present interior floors is considered to be high-very high.

Exterior:Burials expected to be exceptionally high (overflow churchyard below the hill to the east was used in the C19th). Probability of domestic material around periphery of present churchyard.

Interior:Floor levels altered in restoration, but full extent of C19th disturbance unknown. Whole is likely to be highly complex mixture of C14th-C15th building layers with unknown survival of earlier deposits beneath, punctuated by late medieval graves and post-medieval vaults.

Dimensions of the Church

| Greatest length | 215 ft | |

| Greatest breadth | 100 ft | |

| Greatest height | 60 ft | |

|

||

Nave |

||

|

||

| Length | 108 ft | |

| Breadth | 23 ft | |

| Height | 52 ft | |

| Width of Aisles | 20 ft | |

|

||

Chancel |

||

|

||

| Length | 72 ft | |

| Breadth | 35 ft | |

|

||

Transepts |

||

|

||

| East to West | 100 ft | |

| North to South | 35 ft | |

|

||

Tower |

||

|

||

| Height of Parapets | 126 ft | |

| Flagstaff (with 3 ft. vane) | 60 ft | |

The church stands 70ft above the Meadows.