For this church:    |

Southwell MinsterArchaeology

It is convenient to present the minster as having been constructed through four distinctive and separate building projects, three of which are structural, whilst the fourth is a major embellishment: The nave, the crossing and the transeptsThe nave is an illustrated text book on early-to-middle Norman Romanesque architecture. The pattern of columns and arches to be seen at ground level is repeated at the triforium level and at the clerestory level. Everything is strong, solid and enduring – but well-proportioned and pleasing to the eye. Stone originating from within the Late Permian Cadeby Formation, brought from the quarries at Mansfield and Mansfield Woodhouse, is used throughout. The minster is fortunate that any replacement stone required since the twelfth century remains available from the same deposits (though not from the original quarry). After the Conquest, the Norman regime engaged in a flurry of construction. Imposing castles were built to secure and control the countryside and large churches were built to secure and control the religious organization of the country. Southwell Minster is one such building. It was begun in 1108, 42 years after the victory at Hastings. The present church, sometimes called 'The Norman Minster' was built to replace an earlier church on the same site, which is commonly referred to as 'The Saxon Minster'. It is thought to have been located in the general area of the present minster’s south transept and perhaps the eastern end of the north nave aisle, but only tiny possible traces of it are visible today. Much of the Norman nave looks exactly as it would have done in 1170, an estimated date for its completion. Construction would have begun at the eastern end, with the setting in place of the high altar, so if you refer to 1108 whilst standing in the nave make it clear that many years were to pass before the builders reached that spot. The nave is 60 metres long and 18.5 metres wide. The pillars are 4.9 metres in circumference. Zig-zag moulding separates the triforium from the arcading. Tympanum

The stone above the doorway in the north-west corner of the north transept was once thought to be Saxon, but recent opinion dates it as Norman (c 1120). The carved figures illustrate David wrenching open the lion’s jaws, with the lamb above, on the left, and in the centre St Michael confronting the dragon. A tympanum fills the space between a horizontal lintel and a curved arch, normally showing symmetrical geometry, but this one is very irregular and may have had another use at some time. It was lent to the Hayward Gallery in 1984 for the Exhibition English Romanesque Art 1066-1200 and whilst removing it from its position above the door in the north-west corner of the north transept in order to prepare it for the journey, some geometric carving underneath was revealed. Upon its return, the tympanum was remounted to display both carved surfaces. Capitals of the east crossing piersCapitals on the east crossing piers are decorated with stories from Christ's life. They have been dated to the first quarter of the 12th century: Kelly (1998) suggests a more precise date of the second decade of the twelfth century.

The general appearance of the nave transcends the centuries, but there are, however, several features which are of later date. Windows

Only the most westerly window in the north nave aisle is original, but there are six others in the Norman style which were rebuilt in the 19th century to the same dimensions. The four larger windows in the Perpendicular style at the eastern end of each of the aisles were inserted in about 1380 to provide more light. A further change occurred in the middle of the 15th century, when the great west window was inserted. It is a very fine seven-light Perpendicular window, but it has altered for ever the original Norman façade at the west end, which was very plain in style with small windows. In the 1860s, during the period of major renovation and restoration of the minster by Ewan Christian, Architect to the Ecclesiastical Commissioners, the dilapidated condition of the eight perpendicular windows at the east end of the nave became a concern. Christian wanted to replace them with Norman windows and restore the north and south walls to their original appearance. He was over-ruled by the commissioners and had to rebuild them. Ceiling

The barrel-vaulted ceiling was constructed in 1880, but in this case the late work matches the Norman architecture beautifully. It is believed that Ewan Christian, the architect at the time, attempted to reproduce the original form of ceiling. The style of the stonework in the crossing and the transepts matches that of the nave, whilst the barrel-vaulted ceilings in the transepts are scaled-down versions of the nave ceiling. Everywhere one sees solidity, symmetry and consistency. The north porch is a miniature masterpiece and it has not been tampered with in any way. It is rare for a porch of this date to have survived and even rarer for such a structure to be on the north side of the nave. This must have been done because the whole of the town was on that side and it probably reflects a view that the minster’s parallel function as a parish church was of equal importance. Those who visit the minster for the first time see a beautiful and majestic Norman Romanesque structure (nave, porch, crossing, two transepts and three towers) which has remained (except for some window insertions) unchanged since it was completed some eight hundred and fifty years ago. Whilst the non-Norman windows are obvious, it is still possible for the mind’s eye to visualize the appearance of the building in 1200 AD. Since the builders of large churches often took over fifty years to complete their work, they often incorporated new design features as and when they became available, or perhaps a new team took over part-way through and made alterations in the later work. The period we are thinking of (1100 to 1200) was a time of innovation in architectural design and the master mason in charge of the Southwell work might have been tempted to dabble with new things as he went along. He did not do so. Southwell Minster’s Norman nave, crossing and transepts are remarkable for the uniformity and consistency of their style and for the enduring skills of their builders. Changed fashions were specifically not incorporated, and therefore the western half of the present building is coherent throughout its length and breadth. The triforium arches all look exactly the same, north and south. This is even more remarkable because there are good grounds for believing that the nave was built in an anti-clockwise fashion: east-to-west on the north side and west-to-east on the south side. It should also be noted that, when first built with a Norman choir, the whole of the original minster building would have displayed the same characteristics as the nave does today. The choirAlthough the choir dates from (say) 1230 to 1240, only some sixty to seventy years after the completion of the original Norman building, it is radically different in appearance and feel. Early English Gothic, in all its elegant beauty, is on display here. Slender, clustered columns, sharply pointed arches, lancet windows: everything is more refined and cultured than it is in the nave, crossing and transepts. Whilst the work is now fine-drawn, however, it is still plain: there is little in the way of carved decoration here. Any decoration is discreet and shallow-carved. The choir which visitors see today is a replacement for the original Norman choir. The Norman choir became inadequate because the influence and importance of the minster church in Southwell had grown rapidly over a relatively short period. In those times the choir was for the priests, whilst the nave was for the populace. As the minster grew in importance, therefore, activity in the choir grew still further, whilst the usage of the nave remained the same. The Archbishop of York had created more Prebends (which meant more Prebendaries (canons), more Vicars Choral and more chantry priests). By about 1220, say, the old choir must have been quite a crowded place, with priestly personnel of various kinds active within it. The Saxon minster had been too small – that was why the Norman building had been erected – and now they were finding that the 'new' minster’s choir couldn’t cope. In 1234, it appears, a decision was made to undertake rebuilding – not, it must be stressed, to extend it, but to demolish it and build a bigger one. The new choir was to be more than twice the length of its predecessor and so it was possible to begin work at the eastern end and complete the new chancel and the four new small transepts (chapels) before any of the earlier building had to be disturbed. It is generally accepted that the whole of the old Norman structure must have then been demolished, with the exception of the north and south drum pillars to the east of the crossing (both still visible today). As soon as it became possible after demolition, we believe that the masons began to work from the crossing eastwards to ensure that the central tower was supported as soon as possible. Clear evidence that the new choir was built by working from two directions and then making a join is provided by the celebrated 'step' visible in the fourth bay from the crossing on the north side. The crown of the equivalent arch on the south side is lower than its fellows, with a carved medallion above. The Norman choir had a square chancel end, but its north and south aisles terminated in apses. (The northern one was just to the east of today’s chapter house passage). There were also apses in the east walls of both transepts, their position still indicated by the moulded arches we can see today. These apses may have been demolished at the same time as the choir apses (say 1240), or perhaps that work may have been carried out somewhat later: in any event, there is evidence from chapter records that a chapel was being constructed on the east side of the north transept, to replace the Norman apse, in the year 1260. The new work in fact resulted in the provision of twin chapels, side by side with separate entrances. There was also a single chamber, forming an upper story and spanning both chapels. Subsequently, that part of the minster has been used for a variety of purposes. The twin chapels were amalgamated and the ground floor space was used as a library, then it became the Airmen’s Chapel, but today it is the Pilgrim’s Chapel. The Pilgrim’s Chapel is not part of the choir, being entered from the north transept (but the chamber above it is entered from the choir), but since its construction appears to have been almost contemporary with that of the 'new choir', and as it is Early English Gothic in style, it is appropriate to include it in this section. The chapter houseA decree issued in 1288 refers to the construction of the chapter house and the dilatory way in which the Prebendaries were paying their contribution, so it appears that the work was already underway at that time. The chapter house is octagonal in shape, with large heavy buttresses at the angles and has a vestibule and passage leading to and from the north choir aisle. One of the buttresses fits very snugly against the wall of St Thomas’s Chapel, thereby forming, at the time of completion, a small enclosed courtyard. The east side of the chapter house passage was open as a cloister until the 19th century, when it was walled up and six small windows inserted. It would appear that the passageway may have been completed first, but the chapter house itself displays Decorated Gothic in all its glory. Whereas the choir and the Pilgrim’s Chapel display a limited amount of restrained shallow decoration and some carved foliage, here in this splendidly compact octagonal building we see the finest achievements of decorative carving. These present brief notes are an inappropriate vehicle for a detailed review of the extraordinary variety of leaves, fruit, flowers, nuts, small animals and birds to be seen: there are several specialised publications available and they should be studied in depth. Note, however, that in this chapter house there are no carvings displaying Christian symbolism. The unknown artisans who carved here drew upon the countryside they knew and in which they lived their lives. They were asked to decorate the building and so they did so, in a flurry of inspired naturalism. There are ten Green Men entwined in the foliage – pagan symbolism perhaps – but that only seems to emphasize the importance of the fertile countryside and the proximity of Sherwood Forest. From an architectural point of view, however, the great glory of the chapter house is not the carvings and the sublime decorative effects: it is the ceiling. There is no central pillar, as in most chapter houses, to support this stone ceiling. It presents us with an extraordinary combination of engineering design and artistic design. All the ribs and all the bosses are functional – but they are also very elegant and beautiful. This artfully-constructed ceiling combines with the heavy external buttresses to obviate the need for the kind of thick walls used in the rest of the minster: the walls are slim and the window mullions are slight. There is an impression that if the walls and windows were removed, the building would continue to stand. The pulpitum

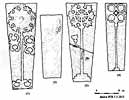

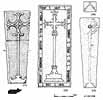

By the year 1300, the Collegiate Church of St Mary of Southwell was structurally complete. No major work of reconstruction or extension was ever again undertaken, or even proposed. A further piece of internal decorative work was executed, however, and that is the choir screen, or pulpitum. A document of 1337 refers to the carting of stone through Sherwood Forest to the minster, which helps to date the work. This stone screen is the most elaborately carved decorative element in the whole church and it represents the high point of Decorated Gothic. There is no longer any plain work visible: every nook and cranny is filled with decoration, including some 280 carved heads. Once again, it is prudent to consult the appropriate written material to absorb the extraordinary detail. The central arch of three on the western side gives entry into the choir and on the eastern side it is flanked by three stalls on each side, each featuring wonderfully carved misericords. The innermost stall on the north side is that of the dean, whilst the corresponding one on the south side is for the bishop. The intricately carved decoration on the bishop’s stall is called diaper work, but we do not know why the other stalls are so plain. The bishop’s stall is often called 'Wolsey’s Stall', because Cardinal Thomas Wolsey (Archbishop of York 1514-1530) spent five months in Southwell during the last year of his life. Medieval cross slabsSlabs (1) – (10) are incorporated in the paving of the western two bays of the nave north aisle, (1) - (4) beneath the arch of the second bay of the arcade, (5) - (9) in the floor of the westernmost bay and (10) just west of the westernmost pier of the arcade. Unless otherwise stated all bear incised designs on Magnesian Limestone. A number of slabs from Southwell were drawn by Samuel Hieronymous Grimm in 1787; these are referenced in the below list, and those which are not now apparent included as nos 20 -24.

(1) Intact slab; impressive but badly-laid-out design, cross with ring head of ten round-leaf bracelets (centre worn but probably had spoke-like arms), with pairs of back-to-back bracelets on each side of the shaft, and two more flanking the base, cf Teversal (4), possibly a North Midlands interpretation of the ‘double omega’ of the Barnack school. (Boutell p.29, Grimm 1). (2) Slab now worn smooth other than vestiges of a round-leaf bracelet crosshead. (3) Intact slab, ring head of eight round-leaf bracelets with spike-like arms, simple stepped base, chalice, unusually set on a tilt, on l. of shaft. (Grimm 22) (4) Cross with head of four broken circles, the stylistic predecessor of the common round-leaf bracelet type; stepped base. (Cutts plate XLIV?).

(5) Upper part of slab with round-leaf bracelet cross with disc at top of shaft, the commonest Nottinghamshire form. (6) Similar design to (5) but intact, with simple stepped base. (probably Grimm 20) (7) Cross with ring head of six bracelets, but with conventional four-arm cross at centre, disc at top of shaft, stepped base (Cutts plate XXIV, Grimm 24). (8) Upper part of slab, very similar to (5) (9) Upper part of slab, faint. Cross pate, with the lenticular segments between is arms projecting beyond the enclosing circle, with on the l. of the shaft the beginning of an arcade of small pointed arches (cf Mansfield 6 and 8 etc). (10) Intact slab. Cross paté rising from spade-shaped base, like a semicircular mount turned upside down. Grimm (6) is probably this slab, although he shows the base as stepped.

(11) Large slab of smooth grey limestone, set in tomb recess in north wall of north aisle, carved in high relief. A high-status memorial; cross with open round-leaf bracelets and facetted panels at centre, rising from base with two more bracelet-like motifs (cf 1). Cutts (plate XLIII) attributes this slab to Archbishop Ealdred who died here in 1069 (Grimm 11). (12) Rectangular floor stone slab beneath the fifth bay of the north arcade, large (2.15 by 0.86 m) and well preserved. Incised design, straight-arm cross with fleur-de-lys terminals with sharply-pointed buds and out-turned leaves, with cusped arms, rising from pedestal-type base. Black-letter marginal inscription to Robert Barbur (?) and his wife Margaret, unusually without any date being given (Grimm 2). (13) One of three tapered slabs re-set in the floor at the entrance to the chapter house (the other two are now plain). Incised round-leaf bracelet cross with four chip-carved panels at centre, and disc at top of shaft, rising from stepped base. Worn. (14) Base of slab now forming internal sill of window on east of chapel on south of choir. Incised, stepped base of cross.

(15) Slab, lacking its head, re-used in external blocking of doorway on east side of south transept. Incised cross shaft and stepped base. (16) Slab lying in churchyard c 15 m south of second bay of nave. Incised design; cross with quatrefoil centre and fleur-de-lys terminals rising from base with steps and a moulded top; interruptions in the shaft suggest it may have been overlain by a label (cf Harworth 1 and 2). Pair of thinly-incised border lines and incised inscription in English, beginning ‘here lyeth Jane Stokman who departed this life ix January anno dni mdcccxliii aetat su lxv. ’….. remainder should be legible with side lighting. This is a real puzzle; are cross and inscription contemporary?. Victorian revival or re-use? (17) Rectangular cross slab floor stone beneath easternmost bay of south arcade, often hidden by chairs. Design very like (12), but considerably shorter – part of the centre section is missing, and replaced in new stone. Straight-arm cross with fleur-de-lys terminals rising from a base incorporating both ‘pedestal’ and masonry forms. Marginal black-letter inscription: ‘Hic iacet Thomas buit (?) qui obit….. mensis Septembr anno dni mil….cccc xxxi ……amen.’

(18) Part of slab 0.65 x 0.38 m re-used in west face of west gateway to Minster precinct, on south of arch and 4 m above the ground. Incised chalice with a scalloped foot. Perhaps later medieval; no other motif visible, perhaps suggesting that was a slab that bore emblems alone, rather than a cross. Grimm (12) illustrates what was probably this slab as an intact slab with chalice (with host above) set towards top and left of centre. (19) In south end wall of same gateway, again c 4 m above the ground. Slab 0.62 x 0.35 m. Incised design, probably an open book. Might this be part of the same slab as (18), as a book often accompanies a chalice as priestly emblems (although the Grimm drawing of (18) shows only the chalice. Slabs drawn by Grimm but now lost:

(20) Tapering slab with semi-effigy (in this case just the head) in a sunk quatrefoil. (21) Tapering slab, decayed, no design visible. (22) Slab possibly in two pieces, upper with cross head of four unbroken circles; lower with cross shaft. (23) Tapering slab with cross of four unbroken circles rising from stepped base. (24) Tapering slab, blank. Grimm also illustrates a further ten slabs (7-11 and 13-17) which are either incised effigies or brass indents.

Descriptions and drawings of the cross slabs courtesy of Peter Ryder. |