For this church:    |

Hockerton St NicholasHistory

The earliest mention of the church is in the Domesday Book of 1086. The former north doorway, visible only from the outside, along with chancel arch, is Norman. In 1251 King Henry III made a grant of land to Rufford Abbey which included some at Hockerton. It is unclear whether this encompassed the land now occupied by the church. In 1291, at the taxation of Pope Nicholas IV, the church was valued at 15 marks (£10) annually and the patronage was secular, being in the hands of John le Butiler (or Botiler). Nine years later, in 1300, Archbishop Thomas of Corbridge issued a commission to the archdeacon, his official, or the dean of Newark to commit the custody of the sequestration in the church of Hockerton to Ralph de Hertford, acolyte, presented by the patron, John le Botiler. In March 1314 Archbishop Greenfield recorded that defects in the nave had been found at a visitation and the parishioners were required to undertake repairs. Archbishop Melton, in November 1330, appointed Henry Asselyn of Halam, chaplain, as coadjutor to Ralph de Hertford, then still the rector of Hockerton, who was apparently 'old, totally blind and physically incapable'. Henry was instructed to make an inventory of the rector's goods and render an account when asked. At the Nonae taxation of 1341 it was stated that the church of Hockerton was taxed at 15 marks and that the ninth of sheaves, lambs and their fleeces were worth 10 marks (£6 13s. 4d.) a year at true value, and that the arable land and meadow there were worth 40s. a year, and the tithe of hay with altar dues was worth 26s. 8d. a year. Hockerton Church, in the York diocese at the time, was assessed in 1428 to pay twenty shillings as part of a Feudal Aid - a subsidy granted by Parliament to King Henry VI. A holy water stoup, presumably medieval, is set in the east wall of the porch next to the door into the church. The Reformation of the English Church begun by King Henry VIII was intensified during the reign of his son Edward VI, whose Privy Council in February 1549 instructed commissioners in each shire ‘to make a true inventory of church ornaments, plate, jewels, bells, vestments etc and to forbid the sale and embezzlement of any part of the same’. The document for Okerton [sic] is in the National Archives at Kew. During her short reign from 1553, Queen Mary sought to revive Roman Catholic practice in the English Church; the rector John Addams was deprived of his position and a Catholic priest, Thomas Huddleston, replaced him. Addams was reinstated in 1559 under the terms of the Elizabethan Act of Settlement. Archdeaconry Presentment Bills refer to the ‘somewhat ruinous’ state of the churchyard wall in 1621; but by 1633, church, churchyard, bells and church appurtenances were in good repair. In 1641/2, as relations with King Charles I deteriorated, Parliament ordered an oath to be administered in each parish throughout England: 40 names were recorded at Hockerton. It is not clear what happened in Hockerton during the period of the Commonwealth when the episcopate was abolished; however, Edward Mason is recorded as rector in 1643 and again in 1679. In post-Reformation England, the ecclesiastical authorities kept a close eye on worship in all parishes. In 1676 Edward Mason, rector, recorded 62 communicants, with no recusants nor dissenters. The conflict between King Charles I and Parliament brought armies and military action to Nottinghamshire as nearby Newark was a Royalist town under siege. Clearly, the church suffered; in August 1684 a Petition was sent to King Charles II for oakwood to repair the roof, damaged during the late civil wars; in December, the Treasury dispatched a warrant to the Surveyor-General of Woods, who reported that ‘the cover of Hockerton Church is so much decayed and rotten that it is propped up within.’ A grant was made of 50 oaks from Sherwood using redwood, designated as unsuitable for shipbuilding. The death of the King delayed matters but the warrant was re-issued in June 1685 by King James II. From time to time the Archbishop paid a visit to his parishes. On the occasion of Archbishop Herring’s Visitation in 1743, the rector was James Gibson, who looked after Kirklington Church too at £16 per annum - ‘an income which I hope Your Grace will not think overmuch for a Clergyman, Even in Celibacy, to Live with a Little Decency and some Sort of Independency.’ There were no Catholics and no Dissenters. In 1764, at Archbishop Drummond’s Visitation, the rector was John Finch. In addition to ministering to his flock, the rector was also a landholder. In June 1786 a Glebe terrier records: Parsonage with 10 rooms and ‘3 garrats’; wash house, brewhouse and necessary. Barn with 2 stables and a pigsty, pigeon loft over. About 40 acres of meadow and arable. Easter dues - 2d per house and garden; 1d per ‘newbear cow’; 2d per mare and foal; 1d per stropper [dry cow]. Charges - 7d churching; 6d burial; 1/- marriage with banns; 5/- marriage with licence. In May 1852 it was planned to rebuild the parsonage with a £680 mortgage from the Bounty of Queen Anne and £240 from the Whetham family of Kirklington Hall. A survey by William Adams Nicholson stated that the walls, roofs, floors and windows were ‘extremely dilapidated.’ The Vestry Minutes for December 1856 reveal plans for the east wall to be taken down, also some outbuildings attached to it; to be rebuilt ‘from chancel to the other corner of the churchyard.’ The expense was to be borne by the Rector and the parish; ‘the wall to begin about three feet high from the churchyard level and follow the slope of the ground.’ The Churchwarden’s Accounts for 1856 contain item for four guineas, ‘half the expense of the wall next the clergyman’s garden.’

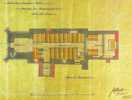

The report of a visit from the Lincoln Diocesan Architectural Society in 1871 noted Norman stonework and an Early English window: ‘some remains of a Norman structure, such as the chancel arch, part of the tower, the doorway within the porch, a corresponding one in the north wall and a little light in the south wall of the nave.’ This article also mentions the large arched recess in the south-east corner of the chancel which served as a sedile; a little canopied niche is set into this recess. The sedile seems to have made use of an old memorial of indeterminate nature which bears an incised inscription in Latin; the words ‘iacet hic‘ are decipherable. In 1868 plans were drawn up by James Fowler, a Louth architect, for a major restoration of the church. The faculty from the Bishop of Lincoln, dated 25 March 1876, shows the expected cost to be £1,000; Mrs Bodham-Whetham, lord of the manor, contributed £300. The chancel was re-roofed, the east gable of chancel rebuilt and the chancel arch repaired. A new south buttress was built. The nave roof was restored, the north door blocked up, and the south wall partly rebuilt with a new porch. The tower was re-roofed and restored, the gallery removed. A new floor was put in and new pews; also a new pulpit and lectern. The font was restored.

In July 1882, £150 was borrowed from the Bounty of Queen Anne for ‘altering and enlarging the farm buildings upon the Glebe.’ White’s Directory for 1894 refers to the interior decoration of the church in 1885. There is slight evidence today of fleur-de-lys design on the chancel wall and a 12-inch wide frieze around the nave wall. Until about 2002, the church was connected to the living at Kirklington. Today, Saint Nicholas’ church has a joint ministry with Holy Trinity, Southwell. | ||||||||||