For this church:    |

|

Reconstruction

of Reconstruction

ofinternal elevation as it might have been in the middle ages |

The Length of the Priory Church

There is no evidence left of the length of the original nave. Nineteenth-century writers refer to it being of seven bays, although without providing any evidence for this figure. Thurgarton’s bay length of approximately six metres is comparable to that of Thornton Abbey in Lincolnshire, but that had an eight-bay nave that was over forty metres long with a width of 9.8 metres compared to Thurgarton’s 9.0 metres. Both were in building during the 13th century, although Thornton followed Thurgarton in date, and it is possible that the churches were of comparable scale

North nave clerestory North nave clerestorynow above roof |

Elevation: Arcade,Triforium,Clerestory.

The evidence for Thurgarton’s three-storied elevation is preserved in the tower, with the bases from one bay of the triforium trapped under the aisle roof The rest of the triforium is visible inside the tower and the clerestory can be seen from the roof above the nave. The clerestory arcade is made up of three equal height arched openings to the church backed by a single window to the exterior. Double chamfered arches and moulded capitals are used throughout (as seen in the Lady Chapel, Worksop), and whorl label-stops (as seen at Southwell and Lincoln).

Roof

There is a large expanse of plain walling above the clerestory, equal to its arcade height above which a high flat or coved wooden ceiling rested on the string course visible just below the weathering for the roof (there is no evidence for a stone vaulted roof). The aisles were also unvaulted; on the aisle side of the north piers there is a shaft and capital to support a ceiling.

Parts of the lost building clearly did have rib vaults since two carved roof bosses and several sections of rib remain in the loose stone collection. One boss is for a junction between a transverse and ridge rib that had moulded ribs, and the other boss is from an asymmetric, five-part vault (another Southwell or Lincoln-derived feature) with chamfered ribs. Both bosses have stiff-leaf foliage decoration and date from the 13th century.

Parallels for the elevation are not hard to find, for example, Lanercost’s east end or Jedburgh’s nave share the clerestory form and their triforia are also similar, but significantly both have an enclosing arch to their triforia, which Thurgarton lacks, although this is common to a large number of other thirteenth-century buildings such as Rievaulx or Salisbury, or more locally, Lincoln.

Tower interior

The bell ringing chamber, the first level in the tower, is reached by a spiral staircase and a cross passage to emerge at the corner of the former triforium level into a large space lit by a large west window. The staircase and passage-way are unusually elaborate for mere access and the triforium arches in the chamber are overly ornate for a usually unseen area.

The east wall of the chamber has an enclosing arch that rises higher than the gallery roof beyond and must originally have framed something more elaborate than a doorway into the roof-space of the aisle. It seems that this area was set aside for a specific purpose, perhaps providing the site for a first-floor chapel, as is the case at Wenlock Priory where such a chapel, dedicated to St Michael, survives at the west end of the nave (although this example is unusual). Upper chapels frequently have dedications to saints having particular connections to high places, in particular St Michael and St Katherine (an altar to St Katherine is recorded at Thurgarton Priory)

The tower stairs have evidence of repair by the insertion of re-used grave markers, especially at the lower levels.

Above the triforium, the present belfry walls appear archaeologically complex and have a large number of putlog holes, beam-slots (evidence for a previous floor level) and projecting brackets. The uppermost level comprises a gallery walkway on all sides of the tower, below the large belfry openings.

Tower and West Front

Thurgarton’s surviving north-west tower is richly decorated with blind arcading and tall lancet windows which extend around all four sides. The gabled buttresses are capped off with stone roofs carved to appear tiled, and the heads of the narrowest lancets have an unusual use of dog-tooth in the chamfered soffits (also seen at Bourne).

Thurgarton had a second tower on the south, of which only one buttress remains, and, although later in date, it therefore belongs to the group of twin-towered facades first built in the area during the Romanesque period such as Southwell and Worksop.

Thurgarton’s west front gable with a row of stepped lancets is entirely the work of Hine, but the join between the original and the replaced stonework is visible beside the north blind lancet, and this enables a reconstruction to be made. The height of the gable can be found from the weathering of the nave roof preserved on the tower, and a row of long lancet windows evidently spanned the gable flanked by tiny blind arches on either side that started at capital height. The lancets had deeply chamfered jambs beneath a more elaborate arch moulding.

Reconstructed ReconstructedWest Front |

Reconstruction of West Front

Two reconstructions are possible: one, based on the east wall at Southwell, uses four equal-height lancets separated by slender shafts; the other, derived from buildings in the north, such as Ripon and Lanercost, uses five stepped lancets. The second version pushes the gable roof-lights higher up the facade and is the preferred reconstruction since the stepped lancets relate better to the height of the ceiling on the interior.

Monastic Buildings

The monastic buildings have mostly disappeared and there has been a house on the site of the west range of the cloister since the late sixteenth century. Both the Tudor and later Georgian house were built over the original ground floor of the claustral west range which survives to the present day as the ‘undercroft’.

Buck’s

engraving Buck’s

engravingdated 1726 |

A date stone, inscribed ‘W C 1598’ (William Cooper) survives as do other stone fragments that belonged to the Tudor house shown on an engraving of 1726 by Buck.

The Buck engraving also shows a large detached building to the south, which is referred to as ‘a magnificent kitchen’ in the antiquarian literature and occupies the usual site for such a building. The present Thurgarton Beck runs under a stone lined bridge at this site and an old stone spout which runs into the stream may be a remnant of the priory kitchen drains.

The present Georgian brick mansion was built in 1777 for John Gilbert Cooper and was extended at both ends by Hine in 1853. It covers the whole of the medieval undercroft – the ground floor of the original west range of the priory – but the ground has been built up to a height of two to three metres and the undercroft windows and doors are now all below ground level. It is obvious that the site used to be terraced and that the ground level of the cloister must have been considerably lower than the level of the church in the thirteenth century, and it would therefore have been possible for the west range to have been of more than two storeys.

The Undercroft

Vaulting

in the Vaulting

in theundercroft |

The undercroft is a rib vaulted rectangular structure supported on a central row of four round piers with moulded capitals and bases, from the middle of the thirteenth century. The ribs are chamfered and rest on corbels on the exterior walls. Each bay is approximately square and has a quadripartite rib vault. The undercroft has been modified considerably with openings changed and walls built that divide up the interior, and the north end appears to have been completely reworked, doubtless during the construction of the house(s) above.

Entrance to the undercroft is through an opening cut through the south wall at the west end of the aisle. An original blocked doorway survives in the second bay from the south and would have led into the cloisters. The medieval undercroft can be reconstructed as a two-cell structure with a central arcade. The main part has five-bays and a total internal length of 18.87m and width of 7.66m. The west range in other priories housed the cellarer’s range and it seems likely that Thurgarton’s was also used for that purpose

Remnants of the Cloister

The floor of the undercroft has risen to the level of the top of the pier bases and there is a step up to a higher level floor on the west side. Slabs of stone forming the edging are from the top of the cloister bench and have a roll moulding to front and back. The cloister bases that would have stood on the bench are set into the bottom of one of the walls built in the post-Dissolution period to divide the undercroft into smaller spaces and only came to light recently when flood water washed the mortar out from between them. Further bases have been recorded in village gardens and all are single circular moulded bases from the thirteenth century. These would probably have supported monolithic shafts and arches to form an open arcade to the cloister garth of a type familiar in the early thirteenth century.

Conclusion

In conclusion, it is evident that Thurgarton Priory had a fine series of stone buildings that were first constructed in building campaigns during the second half of the twelfth century and continued through further works in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries. Stylistically it reflected the architecture of its region, adopting ideas from Southwell, including some that had been derived originally from the most significant building in the East Midlands, Lincoln Cathedral, but also drawing ideas from Bourne, a fellow Augustinian site in southern Lincolnshire, and other Augustinian buildings from further a field. Its current state shows only a fragment of what must have been an impressive series of buildings, but detailed study both of its fabric and of the architectural fragments scattered in the locality enable some impression to be gained of its former richness.

Medieval Cross Slabs

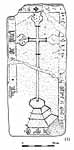

Cross slab 1 Cross slab 1 |

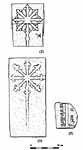

Cross slabs 2, Cross slabs 2, 3, and 5 |

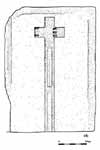

Cross slab 4 Cross slab 4 |

Cross slab 6 Cross slab 6 |

(1) In sanctuary floor, partly concealed by stone supports of altar. Floor stone incised design; cross with odd terminals shaped like thistle flowers (or poppy seed heads?), rising from a badly-drawn ‘three-dimensional’ stepped base. Black letter inscription, only the odd word legible.

(2) Immediately to the south of (1), upper part of well-cut incised slab with eight-armed cross with fleur-de-lys terminals, with on the r. the letter ‘A’ at the beginning of an inscription.

(3) Adjacent to (2), less well cut, what looks like a crude copy of (2)

(4) At north end of floor of sanctuary, large blue limestone slab with indent for simple short-armed cross and marginal inscription in brass.

(5) Piece of slab lying loose against eastern respond of north arcade. Incised cross shaft, remains of black letter inscription, ‘(h)ic iacet mg’ above and ‘ricard tollerlō…… ‘ below. The name may be Richard Tollerton – Tollerton is a village south of Nottingham (pers.com. Lawrence Butler)

Descriptions and drawings of the cross slabs courtesy of Peter Ryder.

Technical Summary

Timbers and roofs

| Nave | Chancel | Tower | |

| Main | Arched braces, probably 1853 | Braced rafter form, 1853 | Planks C19th or C20th |

| S.Aisle | Lean-to C19th, probably 1853 | n/a | |

| N.Aisle | W.end partial C13th valuting otherwise C19th timbers | ||

| Other principal | |||

| Other timbers |

Bellframe

Essentially a Pickford type 8.1.B metal frame by Taylors of Loughborough of 1954 with the addition of X-braces on the east side dating from the augmentation in 2000. Not scheduled for preservation Grade 5.

Walls

| Nave | Chancel | Tower | |

| Plaster covering & date | Plastered probably 1853 but possibly earlier plaster layers below | Plastered C19th, mainly 1853 | |

| Potential for wall paintings | Possible but no visible evidence | None |

Excavations and potential for survival of below-ground archaeology

The excavations of the early churches on Castle Hill are discussed in the text; the potential for remaining below-ground archaeology in this area is VERY HIGH.

There have been no known recent archaeological excavations within the priory church.

The 19th century rebuilding of the chancel had a significant impact on the archaeology in the east area of the church, and the restoration of the nave also had an impact on the surviving medieval portions of the building. The entire church has been reroofed although original vaulting of 13th century date survives at the north-west of the nave, under the tower. A large section of the west front has been reconstructed during the 1850s restoration, although good archaeological evidence for the form of the triforium and clerestory of the priory church survive in the north-west tower. Plasterwork in the nave appears to be 19th century, although it may conceal earlier layers beneath. The north-west tower has survived comparatively unscathed and there is a multitude of archaeological evidence in the interior and exterior fabric. A north porch has been added in the 1850s and much of the medieval stonework has been renewed in this area.

The surrounding churchyard is intact in its parochial form to the north of the church. To the west the land has evidently been landscaped in conjunction with the house which covers the entire south side of the site but which contains important archaeological evidence in the form of an undercroft and associated features. To the east of the present, truncated, church, the land has been extensively landscaped, although the extreme north edge of the line of the church may have survived without too great an impact. The conjectural site of the crossing and priory chancel lie in open, landscaped, grounds, now part of a private residence.

There are considerable amounts of reused carved stonework throughout the site.

The overall potential for the survival of below-ground archaeology in the churchyard and surrounding area, including the eastern portion of the priory church, is considered to be VERY HIGH; below the present interior floors of the nave and tower is considered to be HIGH-VERY HIGH; below the chancel, where there is a possibility of redeposited material, MODERATE. The standing fabric of the nave has been disturbed in the 1850s although medieval stratigraphy clearly still remains undisturbed in parts, the tower contains large areas of undisturbed above-ground stratigraphy, as does the undercroft below the present house: the overall potential for surviving medieval archaeology in the standing fabric is considered to be VERY HIGH.

Exterior:Foundations of the eastern portion of the priory church should remain intact. Evidence of monastic buildings is also expected to survive. Burials expected to be high. Very strong possibility of domestic material throughout.

Interior: Floors disturbed in 1850s, especially at the east end. Whole is likely to be highly complex mixture of C13th-C15th building layers with unknown survival of earlier deposits beneath, punctuated by late medieval graves and post-medieval burials, and intermittent evidence of monastic use.